It’s hard to imagine a clash of cultures more extreme.

In the final year of the 1980’s my eighteenth birthday is spent illicitly drinking beer at a Christian boarding school in St. Louis, Missouri in the flat middle of the United States.

Twelve months later I celebrate my nineteenth in complete silence at a Tibetan Buddhist monastery nestled in the steep foothills of the Himalayan Mountains in Kathmandu, Nepal.

The Royal Nepal Airlines flight touches down on the Kathmandu tarmac with a sudden, jarring bounce. My head is still spinning from the awe-inducing Himalayan landscape I’ve just seen out the window. Standing unsteadily, I move so that the mostly Indian, Pakistani, and Nepali passengers can disembark around me. I’ve been to the Sierra Nevadas, climbed a few 13ers in the Rockies, and explored quaint villages in the Swiss Alps. But now I understand that those ranges are mere foothills compared to the jagged snowy peaks streaked with dark grey that stretched for hours beneath and beyond the airplane. These mountains appear to have no end—they ripple out in every direction, nearly swallowing up the sky itself.

My first sip of the Himalayan Mountain range brew tells me all I need to know—over here, on the other side of the earth, nothing is the same.

Six months earlier I started my freshman year of college, mostly because I had no idea what else to do. After a single semester, it was clear that I wasn’t going to find the answers or direction I was looking for within the walls of an institution, so I dropped out. After twelve consecutive years of school and an ill-advised college enrollment, I found myself limply dragging my mediocre grades and minor accomplishments behind me.

Exactly when had I lost the soaring confidence I’d had when I was younger? Despite my privileged, white, upper-middle-class first-world life I was a confused, timid, mildly depressed version of myself. Entirely unclear about what I was good at in life, what I believed, and what lay ahead of me, I was sick of STUDYING the world. Instead, I wanted to EXPERIENCE it. Although everyone kept asking me what I wanted to major in (I mistakenly thought the answer to that question would determine my entire future), I could barely decide on which of my circle of friends were trustworthy and what music I actually enjoyed listening to.

My mostly sympathetic parents offered a solution: they would front the funds they would have spent on my education that spring semester provided I did some sort of program, ideally one that would offer me college credits. When I learned about a months-long “Experiential Learning” program in Nepal I knew it was for me (I also acknowledge that I was the beneficiary of unusual privilege in that I was able to both attend college and visit Asia in the first place).

A couple of months later I find myself on that Royal Nepal Airlines flight, embarking on the adventure of a lifetime.

I am eighteen years old.

On paper, the details of our Spring 1990 Nepal program are straightforward: the group of approximately fifteen of us will live together in Kathmandu while studying the Nepali culture and language. The itinerary includes a month-long homestay with a Nepalese family, an optional ten-day retreat at a Tibetan Monastery, volunteer time with a local organization, a forty-day trek to Mount Everest Base camp at 17,598 feet in the Himalayas, and a final foray into the rhinoceros-infested jungle in the flatlands of Nepal.

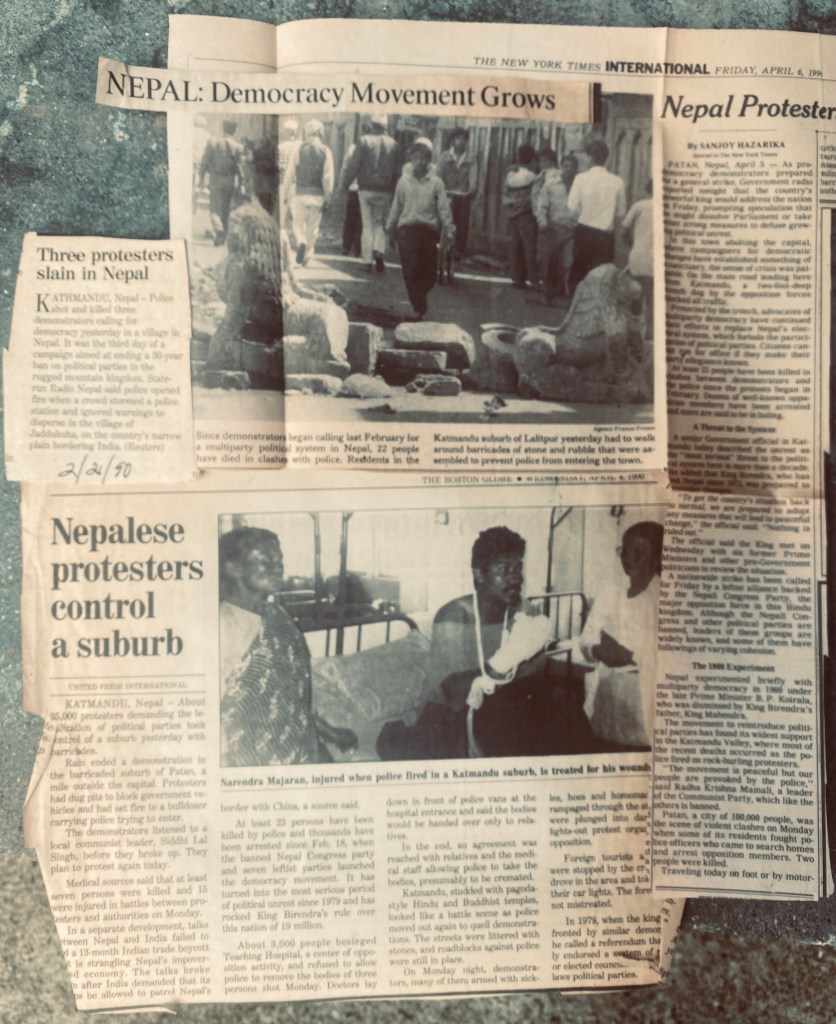

As if that list isn’t enough, something else is going on in Nepal that wasn’t exactly factored into the itinerary: a political revolution. A primarily student-led movement is rising in resistance to the royal monarchy that has exclusively ruled Nepal for centuries. The protesters want a constitutional monarchy (essentially a system of government that limits a King or Queen’s absolute power and includes…wait for it…a constitution). The number of Nepali demonstrators is growing by the day, and protestors are willing to stand up, be shot at, and fight for their independence. Parts of Kathmandu are in turmoil and there are rumblings that our program may be cut short.

press clippings he has carefully saved.

Our bunch of students is a hodgepodge of mostly East Coast characters from the US ranging in age from eighteen to thirty-one. Many of the group are students at Ivy League universities and I quickly learn a valuable life lesson: admission into Harvard or Yale does not necessarily mean one has more street smarts, empathy, or knowledge about day-to-day survival (on the road or otherwise) than anyone NOT attending a top-tier university (or than those not attending college at all).

Because it is 1990 and the Internet is a mere twinkle in a few eyes, my journalist father is back in Boston, Massachusetts closely following the newswires and outlets covering the Nepali revolution. When I return home months later he hands me a collection of carefully cut-out press clippings tracking the progress of the contentious uprising raging along while I am on the other side of the world.

The city of Kathmandu is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the world, and it shows. Unlike countless other countries, Nepal has also never been colonized, so it maintains a sense of ancient identity. My first days are of a dizzying blur of speeding rickshaws, ancient temples on street corners adorned with fresh marigold flowers, unrefrigerated and unidentifiable meat displayed for sale on hooks, zero traffic lights, and bright-eyed children giggling behind their hands as they stare at our Western-style clothing and bumbling sidewalk map-checking (many Kathmandu roads, especially side ones, are nameless which makes navigating especially tricky).

There are also congregating children in rags so dirty I can’t differentiate between their clothes and skin. Small hands outstretched and shaking with hunger or disease, they plead for coins while I empty my wallet and experience multiple existential crises. I’m overwhelmed with disgust at how selfishly I’ve lived my entire life. Me, who knows the deep and unconditional love of my rare family, who was gifted a safe birth in a free country with every advantage. Who am I to complain about receiving an education, in fact to complain about ANYTHING at all?

And there’s something else: for the first time in my life, my white skin puts me decidedly in the minority. Experiencing this shift feels important and humbling.

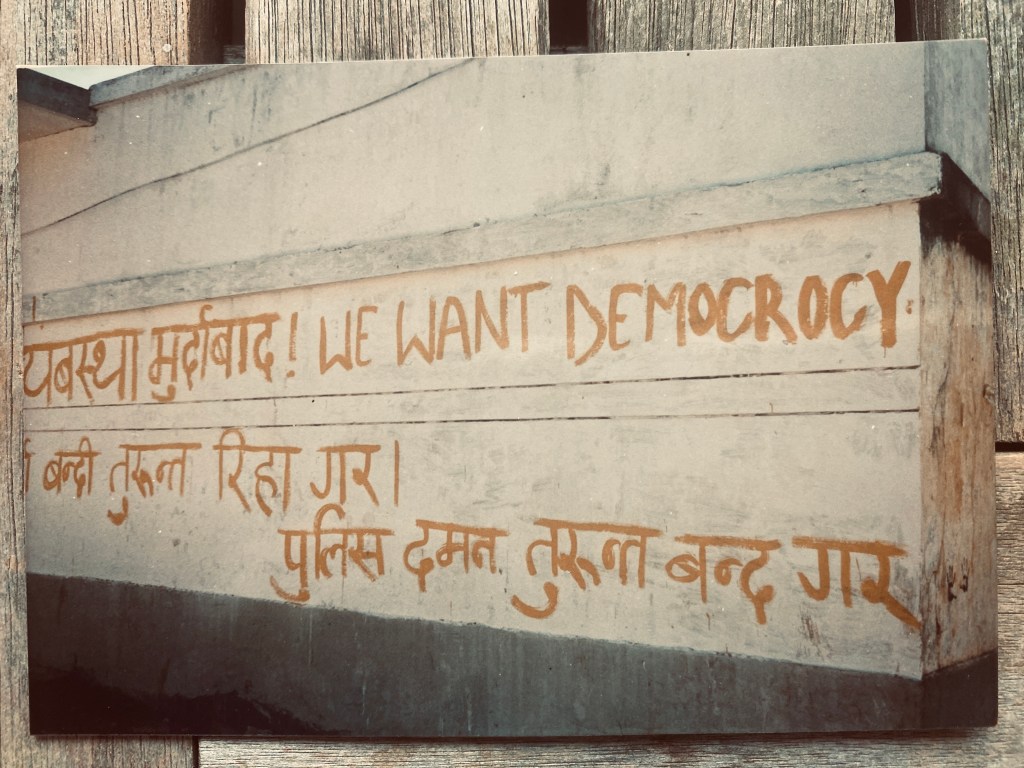

There are hints of the revolution everywhere—khaki-clad rifle-wielding police on street corners, scrawled graffiti pleading for freedom, whispers by our Nepali language teachers about friends and family who have been arrested, and later, city-wide shoot-on-sight curfews enforced after dark. Still, the (American) leaders of our group work hard behind the scenes to keep us safe. We have all come this far and aren’t about to step out early. We meet with foreign journalists in Nepal who are covering the revolution, and they explain to us the history at play and the dangerous realities faced by the Nepali protestors. I begin to see the freedoms I enjoy in the United States in a new light—could I be taking my country’s freedom of thought and action for granted?

-Citizen Ward 29″

The surprises keep coming: Wooden storefronts and squat concrete buildings lined dusty unpaved streets teeming with sari-wearing Nepalis, Indians, and European and Australian tourists (American tourists are less common). Dusty, radiant, smiling kids offer us gum, tug at our shirts, and ask us to play with them. Occasionally, cows so skinny their bones protrude lumber unbothered down the street. I learn that Nepal is 80% Hindu, most Hindus are vegetarians, and cows are considered sacred in the Hindu faith. Everyone leaves the cows alone. But where are those cows headed, I wonder, and how do they know how to get home?

Another unusual sight: young men around my age strolling as they clasp hands with other men. When I ask about this during my Nepali language and culture classes I am told “These men hold hands with each other as a sign of affectionate friendship.” This singular example of a common Nepali custom is a revelation to me. I try to imagine young (straight) American men strolling down the sidewalk on a sunny day holding hands with their best bro… and fail.

An important aside: Nepal has a complex history with LGBTQ+ rights. A landmark 2007 case identified the “third gender” as a legal category on their country’s census (Nepal was the FIRST COUNTRY IN THE WORLD to do this), as well as inclusion on voter rolls, and even passports. Despite this, discrimination and intimidation toward LGBTQ+ citizens in Nepal remain rampant into the present day.

Our motley group lives in Durga Bhawn, an aging palace that formerly belonged to a Nepali honorary. Nicknamed “the Durg,” we attend daily language classes there and learn useful words and phrases (although a surprising number of Nepalis know English) beginning with the ubiquitous “Namaste” greeting (meaning “I salute the God in you”) and ranging from apaal=hair to thik chaa=okay. The group slowly gets acquainted with each other and forms friendships and alliances with the Nepalis who teach and care for us. I gravitate toward another student on the program—a vibrant, independent, funny long-haired girl who walks on the balls of her feet, studies in Oregon, and is always up for adventure. Jess and I become close friends, never imagining that our friendship would still be going strong decades later.

Slowly, as we get to know our surroundings, the complex history Mother Nepal holds close to her heart unfolds. A Feb 16, 1990, entry in my journal records an encounter with a Tibetan woman who cleans the guesthouse where I sleep the first few nights:

“I was sitting on my bed this afternoon catching up on some letters and cleaning/organizing. I took my first warm shower today since arriving, and it was heaven. Suddenly, in came a woman. I had semi-met her before although I still don’t know her name. She cleans our room each day, and many of the other rooms, I think. She sat down on my bed. We said hello to each other and smiled. She asked my age and couldn’t believe I wasn’t married. Then she told me she has a 19-year-old son and wants me to be his sister (I hope she didn’t mean wife!). She invited me for tea at their house. I said okay. She said okay. I finally understood she was trying to tell me she was Tibetan. She showed me a necklace which I think signifies her nationality. Then she said “No husband, no father, killed, bam bam.” She made a sharp noise like a shot and a gun with her fingers. I felt awful. She must have left Tibet with her son and fled to Nepal.”

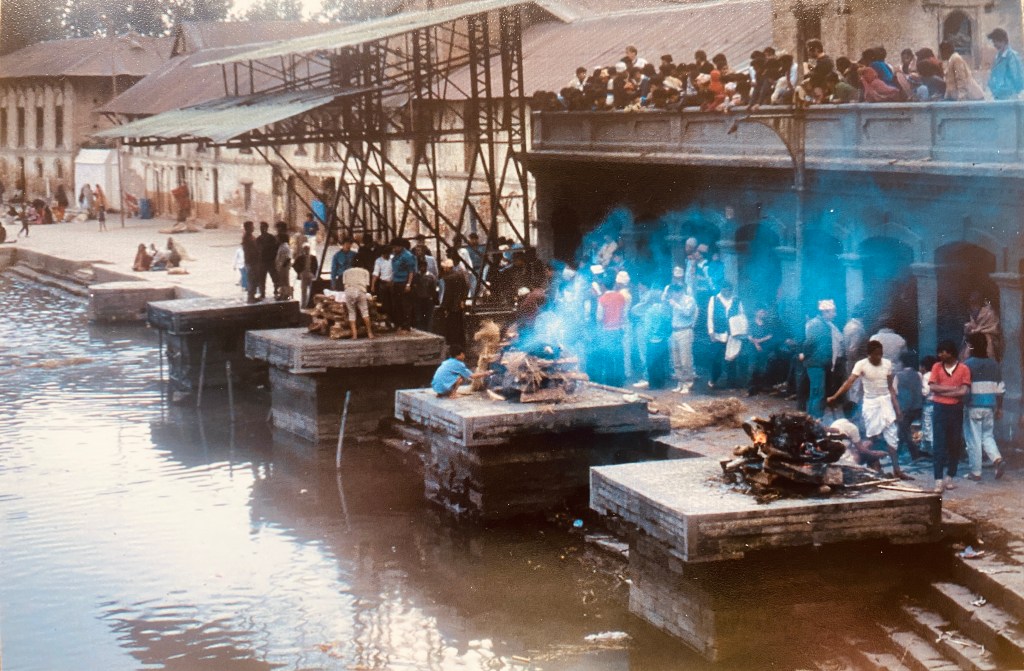

One Sunday a few of us decide to take an ambling walk to the Bagmati River, the central, holy river flowing through the heart of Kathmandu. We are headed toward the famous Pashupatinath temple, but l have little idea of the impact the visit will have on me.

As we set off the smattering of pedestrians surrounding us on the streets quickly swell into crowds more pressing than any I’ve experienced. By crowds, I mean thousands of humans crammed so closely together that I can feel the dampness of their clothing, smell their most recent meals, and note the fine details on women’s jewelry. An unknown scent wafts through the air, smelling of woodsmoke and something else sweetly pungent.

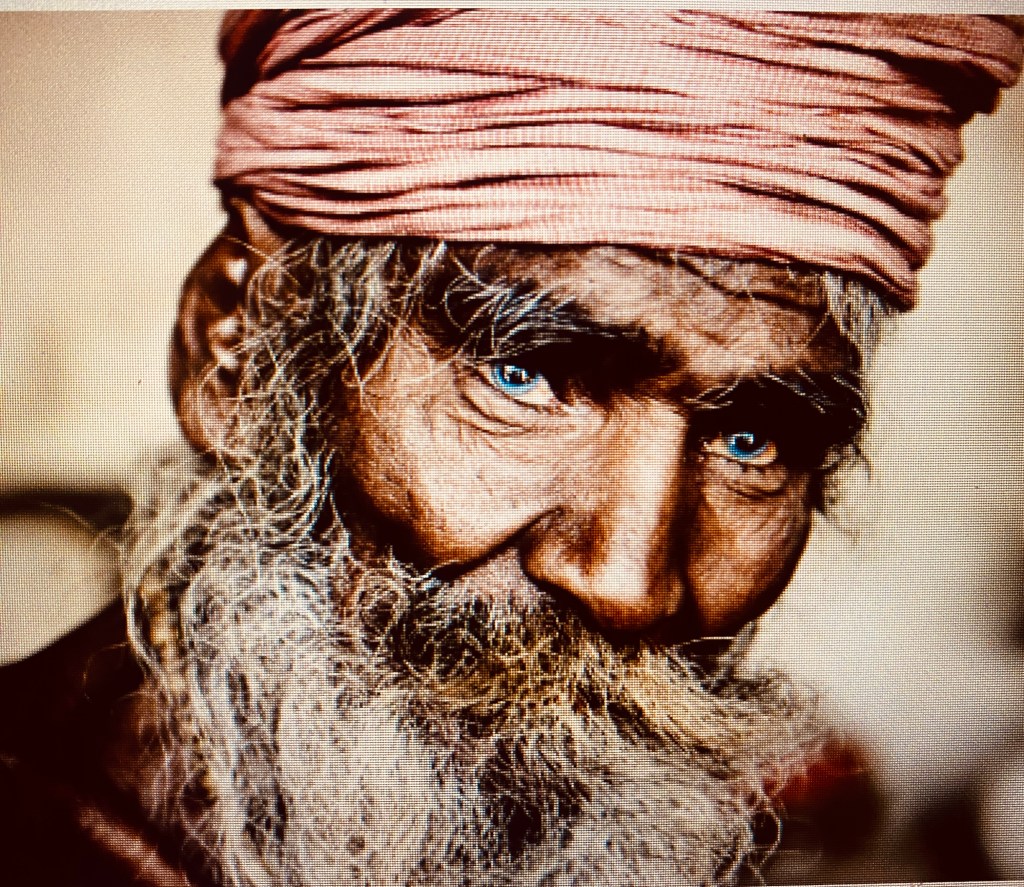

The crush swallows us as we walk, carrying us forward and depositing us on a wide bridge over the expansive Bagmati. Up ahead I notice people adeptly parting around a man sitting on a box in the middle of the span. Stopping short in front of him, I find myself staring at a human unlike any I’ve seen before. Wrapped in vibrant orange fabric, his skin the color of burnt copper, piercing blue eyes peer out from his painted white face. Long dreadlocks hang at his sides, extending well beyond his sweeping white beard. “He’s a Sadhu,” my friend whispers over my shoulder. “He’s renounced all worldly possessions and took a vow of poverty—they do it so others can practice their good karma.” The expression in the man’s eyes makes me shiver—it’s as if he is peering through layers of my soul.

Credit: Getty Images

I hardly have time to register this marvel before the mysterious smell I’d noticed earlier becomes too strong to ignore any longer. Turning to my right, my gaze follows the coffee-doused-with-creamer-colored river water as it flows out from underneath the bridge. Rows of temple towers cluster along the banks on either side and in front of them are what appear to be a series of large bonfires, flames licking insistently at the wood. Wizened men are stooped over tossing sticks onto the piles, creating ever higher stacks. Suddenly, it is clear to me that these are not bonfires, they are funeral pyres. At the top of each stack, a charred human body stretches out, burning in tandem with the black wood. The mysterious smell filling my nostrils is seared human flesh.

Later, I learn that the very spot where we stand is most sacred to both Hindus and Buddhists. Hindus carry their dead to this holy place, dipping the bodies three times into the Bagmati, and then carry out cremations on these pyres lining the river. Reincarnation is a tenant of Hinduism and all around people are ushering their loved ones into their next chapter in the most respectful and holy way they know.

Staggering out from the other end of the bridge I separate myself from the throngs and slump beneath a tree with my spinning head held in my hands. Witnessing this holy tradition and level of devotion leaves me feeling stunned, deeply honored, and questioning everything I know about Western faith and end-of-life practices.

And somehow, despite the smell of death and the press of humanity surrounding me, I feel perhaps more alive and inspired than ever before.

Nepal is quickly becoming my greatest teacher.

You must be logged in to post a comment.