-

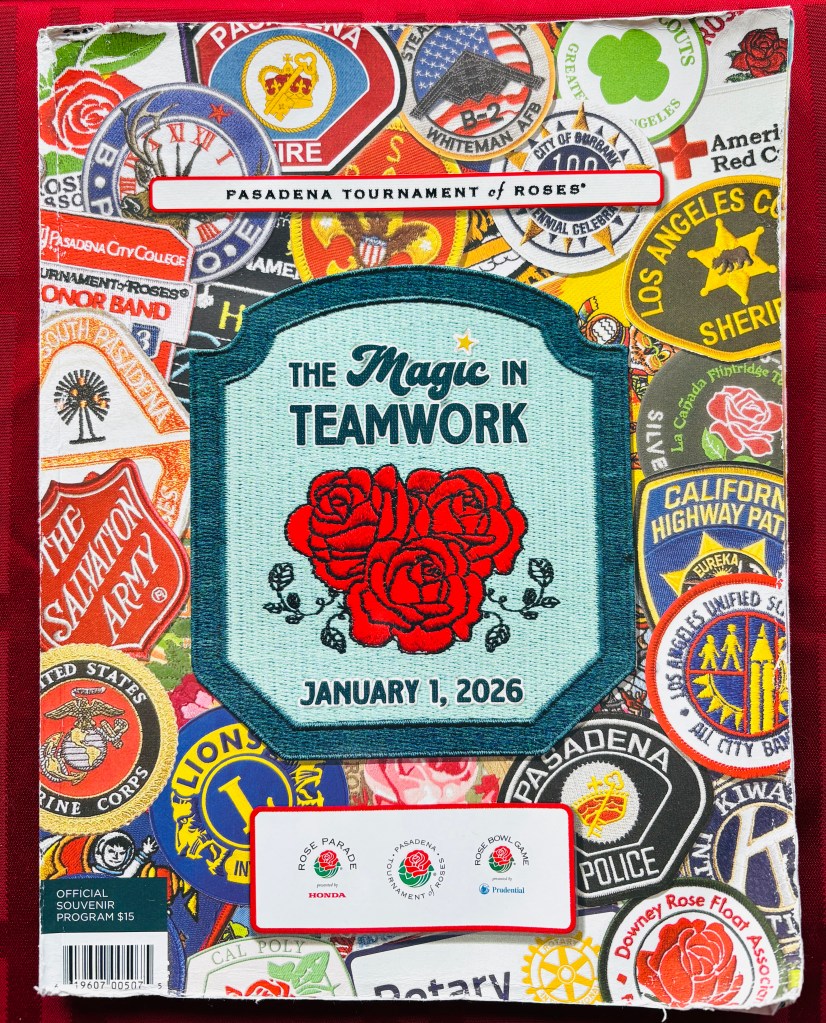

Two Girls at the Rose Parade, 40 Years Apart

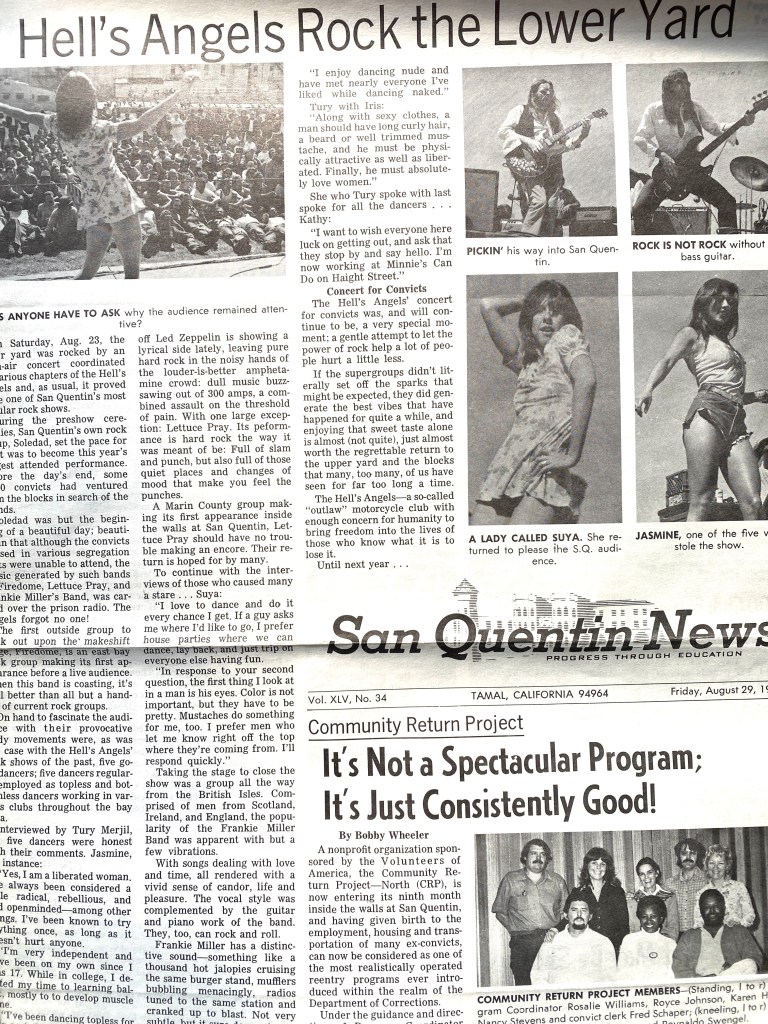

1926 Tournament of Roses “Prizewinners” pose, 50 and 100 years before our story takes place Pasadena, California, January 1, 1986, 5:15 AM:

I wake to the sound of my dad’s voice—hushed and gravely. “Kiddo, time to get up. We’ve got to get out there early so we can get seats. Melba has some cereal for you in the kitchen.”

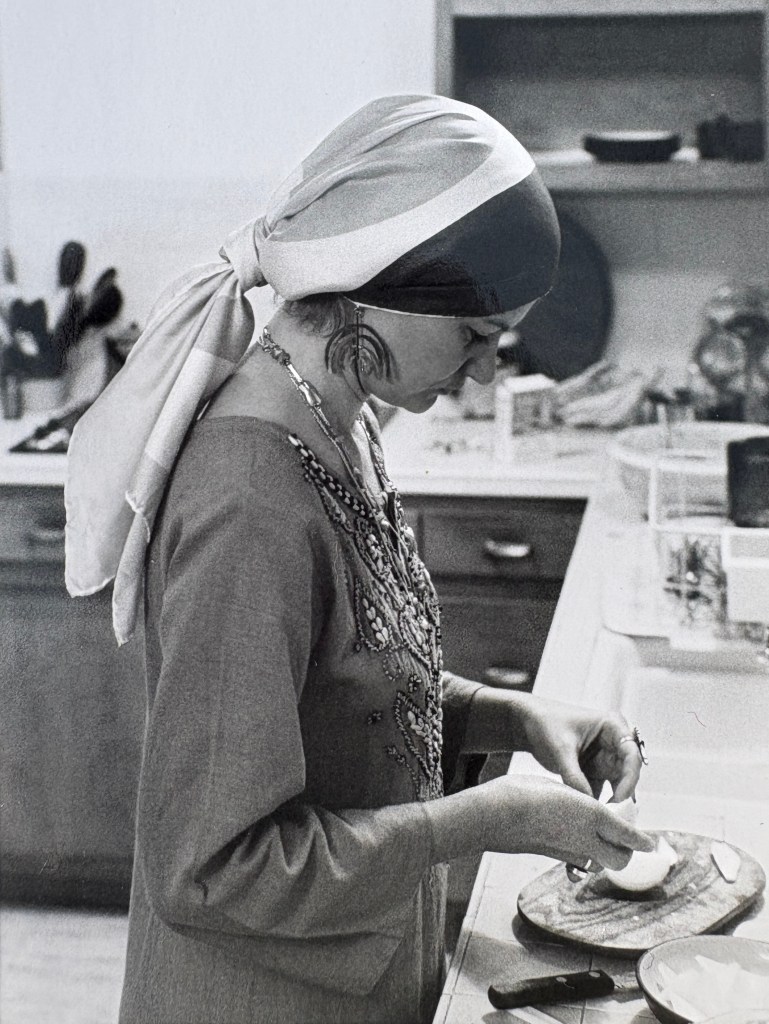

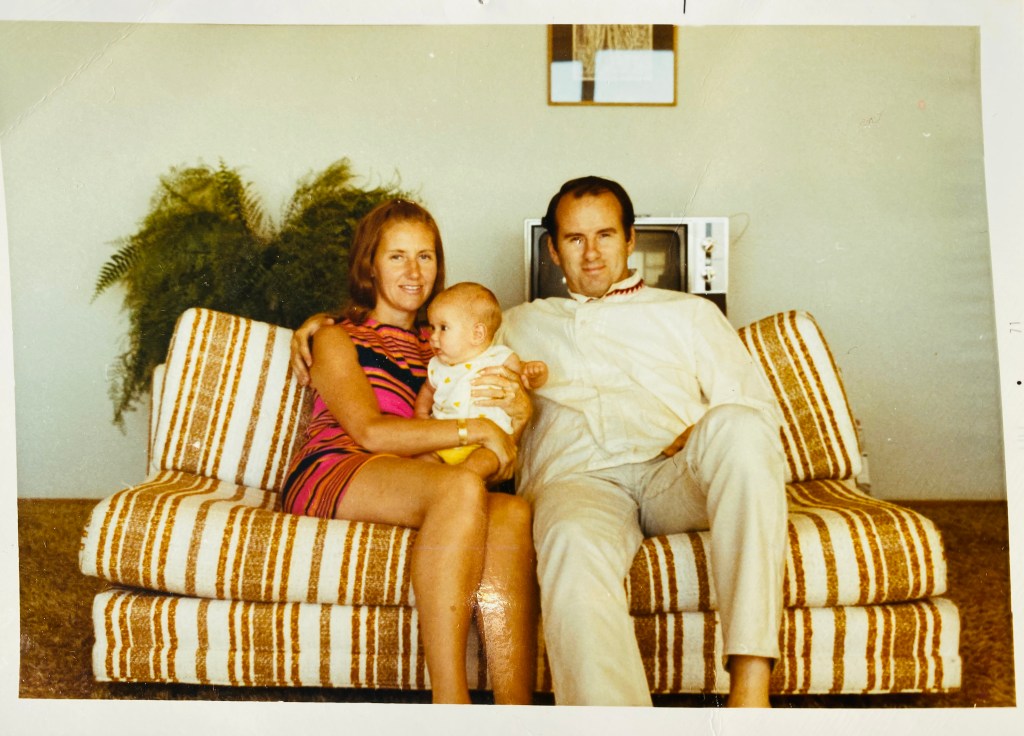

Sleeping on the polished wood floor of my grandparents’ tidy Pasadena bungalow hasn’t exactly made for a restful night. Slowly, I roll over and open my eyes to the darkness of the living room. As I wiggle out of my sleeping bag, I remind myself that there’s a lot to look forward to. Today is the first day of 1986! I’m turning 15 in a few months! I get to watch the Rose Parade in person! And unlike my chilly, often rainy-in-the-winter hometown in Northern California, today will be sunny and warm. This is LA, after all. I head to the kitchen to eat Wheaties with my dynamic, turquoise-collecting, organ-playing step-grandmother, Melba.

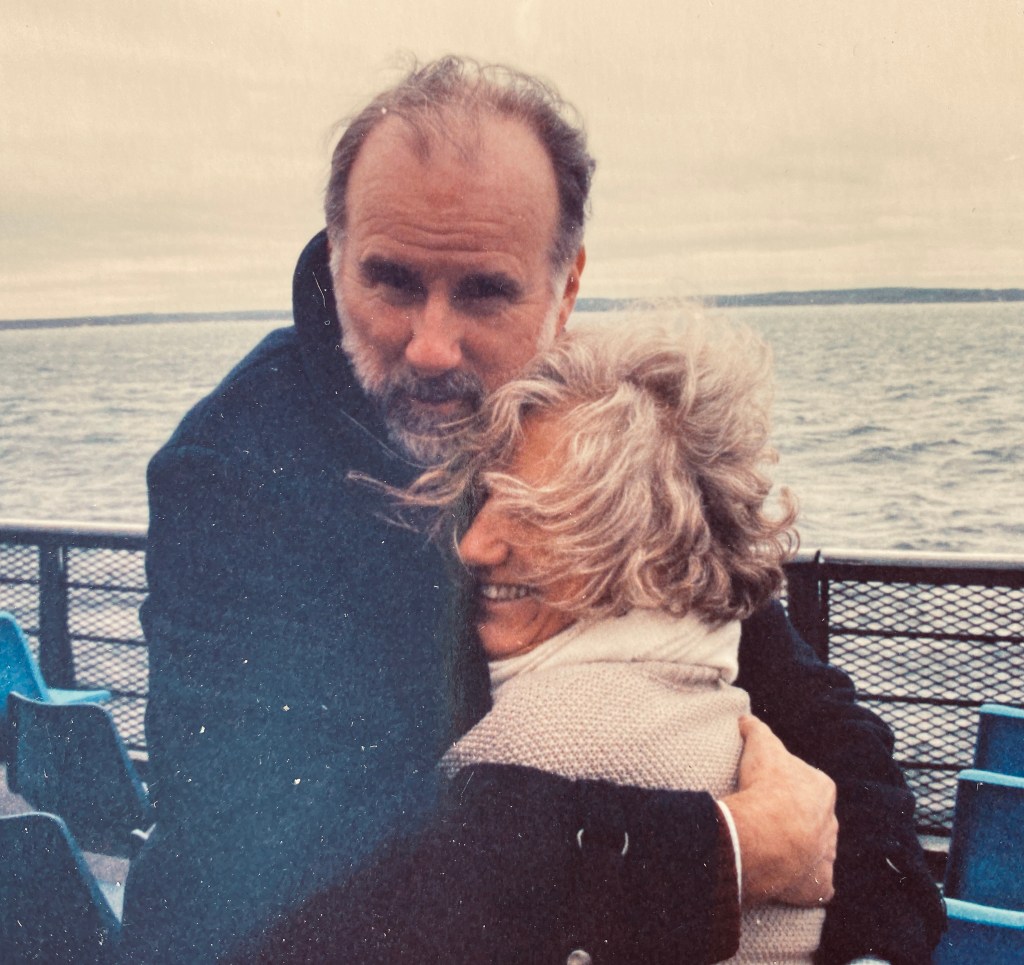

Me and Melba (a few years later, in 1995) Pasadena, California, January 1, 2026, 5:15 AM:

A few seconds after swiping the bar to silence my cell phone alarm, I roll over and gently nudge my 12-year-old daughter’s shoulder. “Time to wake up, Bunny…it’s the first day of 2026! Dad’s got a blueberry muffin for you in the kitchen.” Groaning, she shakes off my hand. She’s not easy to wake up on the best of days, but this morning I fear that the combination of the 3-hour change from our Midwest home, plus an ungodly wake-up time, might make it impossible. The driving rain outside doesn’t help either. Not fair, we’re in LA!

To claim our prepaid parking spot for the Rose Parade, we must arrive by 6 AM. The sun won’t rise for hours over the spacious modern house we are staying in—a house belonging to good friends who are out of town. And thanks to the unusually heavy rain sweeping across the Los Angeles basin, we won’t feel the sun on our skin for almost the entire day. With the promise of an early visit to Starbucks, our daughter finally rises. Blurry-eyed, mostly silent, yet eager to experience the parade. She refuses the muffin.

Los Angeles sunset as seen from the modern house’s kitchen 1986, 6:30 AM:

After piling into our blue Honda Accord, my dad steers the three of us (Mom, Dad, and me) the few miles from my grandparents’ house on Arden Drive to Colorado Street in downtown Pasadena. We are meeting our family friends, Kathy and Phil, at the parade. I am particularly fond of Kathy and Phil. The two of them live (child-free) in a house on a steep hillside above the Russian River, where banana slugs leave thin gossamer trails. However, they also once lived out of a school bus full of intricately handmade wooden cabinetry stocked with Mexican beads that was parked in our driveway for a month.

Kathy Toomire, 1982 It’s early enough that we easily find a parking space, but incredibly, many of the prime viewing spots along the parade route have already been claimed. My parents good-naturedly refuse to pay for “overpriced bleacher seats.” As our group stands on the curb discussing what to do, a truck suddenly pulls up next to us, and a burly guy leans out of the driver’s side window. “Hey, we got couches for rent,” he yells. “We’ll drop it off on the street right here and pick it up at the end of the parade. Thirty bucks!” The grownups look at each other, unsure about the offer. I quickly pipe up, “Oh please please please, that’ll be so fun!” Everyone agrees, and the five of us soon find ourselves sitting thigh-to-thigh on a fake leather couch, unexpectedly granted a rather cushy front-row seat to the 1986 Tournament of Roses Parade.

Seated on our parade-viewing couch, from left: Phil, Kathy, Mom Patricia, me, Dad David 2026, 6:30 AM:

“Two hot chai lattes with oat milk, one hot cocoa, and a croissant, please.” As one of the few cars in line, we quickly move along the Starbucks drive-through and are soon pulling into our assigned parking space, right on time. Our (uncovered) bleacher seats are only two blocks away, and the parade starts at 8. There’s only one hiccup—it’s raining. Hard.

We are prepared. The day prior, after trying four separate stores, we were finally able to purchase plastic rain ponchos (never mind that we now appear to be huge LA Rams fans). We are also equipped with plastic garbage bags to sit on, snacks, and a change of clothes. My husband, who is attending the Rose Bowl football game after the parade, has his own see-through bag packed complete with regulation-sized water bottles and a towel. We waive off the friendly lady weaving through the nearly flooded parking lot, offering Rose Parade seat cushions for $20 each.

Sitting in the dark, we listen to the rain drum on the car windows and sip our warm drinks. Our breath builds steam as we stretch out with the ease of the early hour. I’m grateful to share this cozy time with my daughter and husband. These quiet moments with our girl are fleeting—she’ll turn into a teenager this year. I can feel her consciously shaping her own identity apart from us, no longer attached to my hip or sharing every detail of her life with me the way she once did. She got her first phone for Christmas this year. Turning to ask her something, I see that she’s stretched out across the backseat, her head resting on a rolled-up sweatshirt, sleeping soundly.

1986, 8:00 AM:

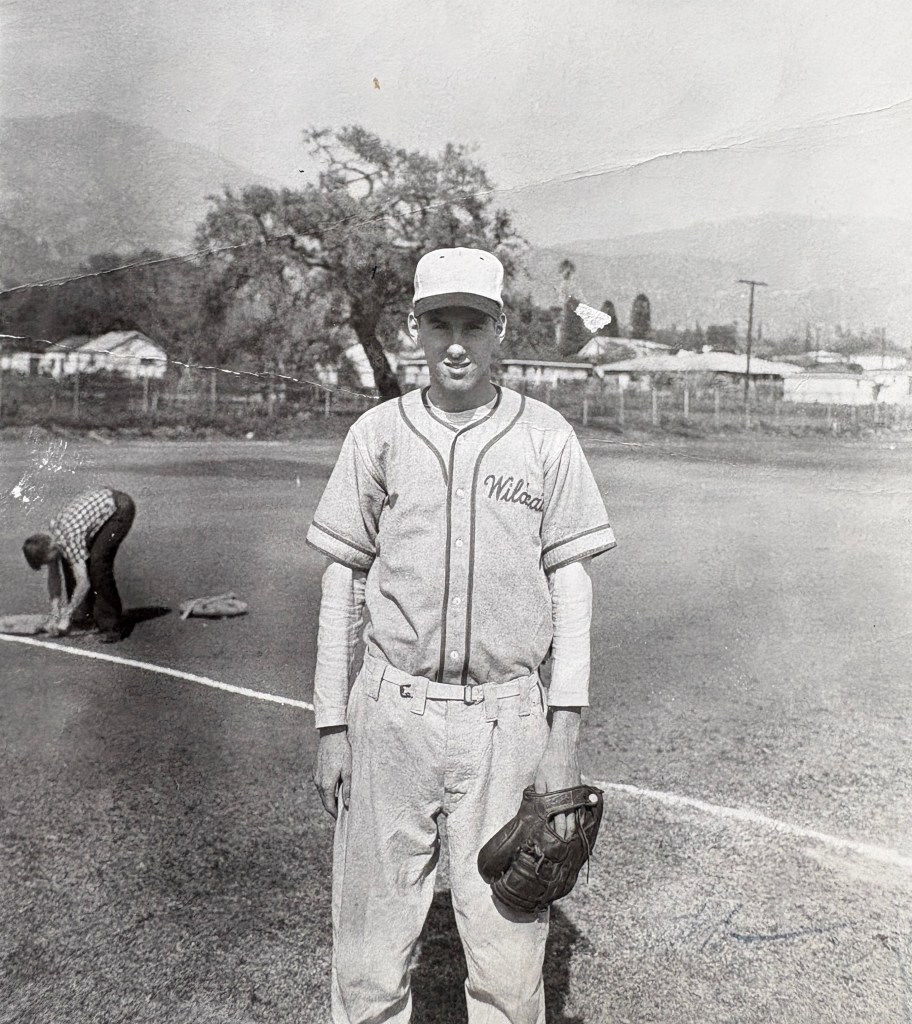

The Pasadena City College band marches by, mere inches from our crossed ankles, the blaring horns and drums making my head throb. “Did I ever tell you I went to Pasadena City College before I went to Principia?” asks my Dad. I roll my eyes (a common occurrence), “Yes, Dad, many times. I know you played baseball for them, too.”

He clears his throat, then his thoughtful gaze shifts to mine. “What would you think about taking the Honda over to the Rose Bowl parking lot tomorrow? If it’s not too crowded, you could practice the stick shift a bit.” My eyes grow wide. “Really?” I ask incredulously, even though I know he wouldn’t ask if he didn’t mean it. My dad never goes back on his word.

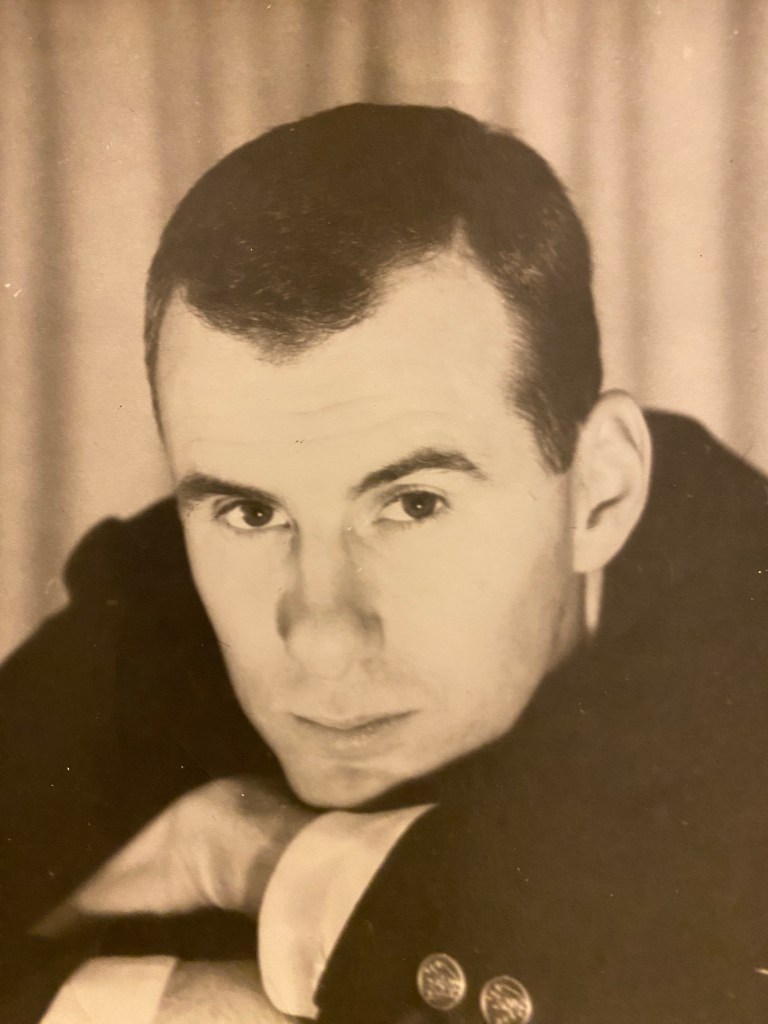

My father the pitcher, Monrovia, CA 1956. His greatest claim to fame was not his sucessful career as a journalist,

it was the time he once pitched a no-hitter.This Grand Marshal of this year’s 133rd Rose Parade is Mickey Mouse, tying in perfectly with the theme: A Celebration of Laughter. I’ve been to Disneyland once, when I was three, but not since. My dad is a freelance writer, and our vacations are almost always centered around visiting family or camping. I know better than to ask for a trip to Disney—there isn’t a budget for that.

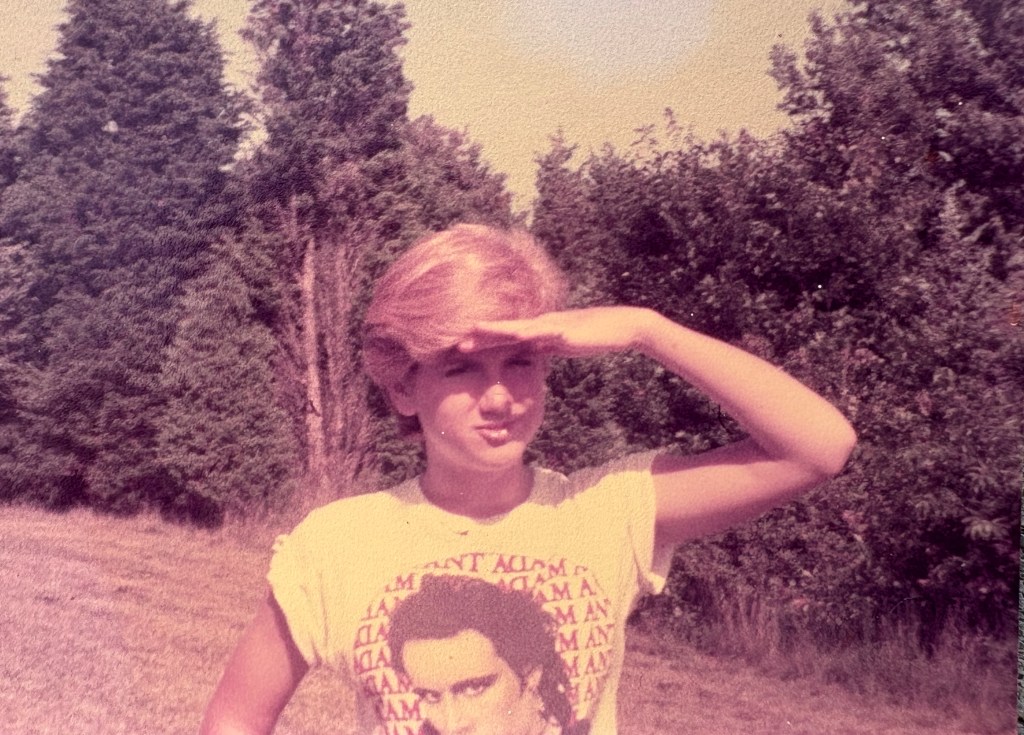

Mom, Dad, Kathy, and Phil point out the flower-covered floats, plentiful prancing horses, and celebrities. The sun is out and beginning to warm the excited parade crowd. After a while, I lean against my mom, close my eyes, and turn up the volume on my Walkman. The parade is entertaining, but I’m tired. I’ve never been much of a morning person. Right now, I’d rather be at home, calling my friends on the phone and listening to Adam Ant.

Adam Ant fan, 1984 2026, 8:00 AM:

Still in the car, we’ve been waiting for a break in the rain, but it hasn’t arrived yet. Parade start-time is approaching, so we pull on our ponchos, ready our bags, and step out into the downpour. At least it’s daylight now. Suddenly the festive atmosphere surrounds us. I get the sense that this is about as friendly a scene as you’ll find in Southern California.

We walk the two blocks to our assigned bleacher seats, avoiding puddles and trailing behind a group of young Latino men yelling into a microphone about the importance of fearing Jesus (what would the all-loving Jesus say about that advice, I can’t help but wonder).

Above us, a large squawking flock of Pasadena parrots flies by, a welcome distraction from the rain. This flock is much higher in number than the flock that used to fly above our San Francisco cottage.

Look closely to see the parrott fly-by We’re up in the 20th row of metal bleachers ($336 for three seats, parking, and one program). The garbage bags we brought have come in handy, and we place them across the soaked seat. Behind us, a young girl is on the lookout for her dad, who plays the clarinet in one of the marching bands. Directly in front of us is a couple sharing our love for the Indiana Hoosiers, playing in the Rose Bowl football game in just a few hours for the first time since 1968. How wonderfully strange it is to travel across the country only to be surrounded by people connected to our own Midwest hometown and team.

Around us, the damp crowd stirs as the first rose-bedecked motorcycles cruise by. The 137th Rose Parade is starting! One clever, vibrant float after another sails by, horses of every breed and color (from the Budweiser Clydesdales to mini therapy horses from Calabasas) and the most impressive, inspiring marching bands we’ve ever seen in a parade.

One band, the Allen Eagle Escadrilles from Allen, TX, includes so many members (600) that they create a royal blue sea stretching down the road as far as the eye can see.

The Allan Eagle Escadrilles from Allen, TX take over Colorado Street My daughter is particularly impressed by the perpetually waving lovely 2026 Rose Court, the elephants on the San Diego Zoo Safari Park (announcing the park’s new Elephant Valley attraction), and the stack of hot syrupy pancakes featured on the City of Sierra Madre float.

City of Sierra Madre float My husband and I enjoy the gorgeous City of San Francisco float (our former hometown), the Star Trek 60 “Space for Everybody” float featuring a grinning George Takei and Tig Notaro, Apple TV+’s Shrinking float (one of our favorite shows, shot in Pasadena—where are Harrison Ford and Jason Segal and Jessica Williams??), and a glimpse of the great Earvin “Magic” Johnson, the 2026 Pasadena Tournament of Roses Grand Marshal, still going strong at 66 years old.

City of San Francisco float

Impressive Baobab trees on the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance float

Delfines Marching Band from Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico

Parade Marshal Earvin “Magic” Johnson, basketball legend.

His hand is the right size for effective waving.Through the rain, the brave parade participants wave, drive, clop, and march. Under her poncho, my daughter texts her friend, “Can’t talk now, I’m at the Rose Parade.”

1986, Noon:

Walking up the low concrete steps leading into my grandparents’ home, the five of us feel hungry, tired, and overstimulated. My step-grandmother Melba has made us soup and sandwiches, and we eat together in her immaculate kitchen, bright Los Angeles sunshine reflecting off the yellow walls. Phil regales us with stories of his wayward youth in San Diego. Across the room, my towering Swedish Grandfather winks at me, his kind blue eyes crinkling at the corners.

Afterward, collapsing on yet another couch, I lean heavily against my mom. I might be fourteen, but in many ways I’m still her little girl.

2026, Noon:

The parade has ended, and for the most part, so has the rain. Walking carefully down the bleachers, we make our way to the street, where we part ways with my husband. Father and daughter hug tightly, and we tell him to enjoy an experience he has been dreaming about since he was a child, his Indiana University team playing in the Rose Bowl. (Not exactly a) spoiler alert—they won.

The Indiana Hoosiers’s second appearance at the Rose Bowl since 1967

Photo Credit: Tom StrykerWeaving through the parade stragglers, we head in the direction of our car. The two of us are hungry, tired, and overstimulated. While her dad walks down Colorado to catch the shuttle to the Alabama vs Indiana Rose Bowl Football game, my daughter and I head to Glendale where we have tickets to see the final episode of Stranger Things on the big screen.

A few hours later, reacting with emotion to her favorite character’s shocking demise, my daughter leans heavily against me in the dark theatre. She might be twelve, but in many ways she’s still my little girl.

Daughter and Dad explore Griffith Park, December 30, 2025 Thanks for the memories California, you know how to throw a parade, no matter what year it is. We’ll be back soon. Hopefully the sun will be out.

-

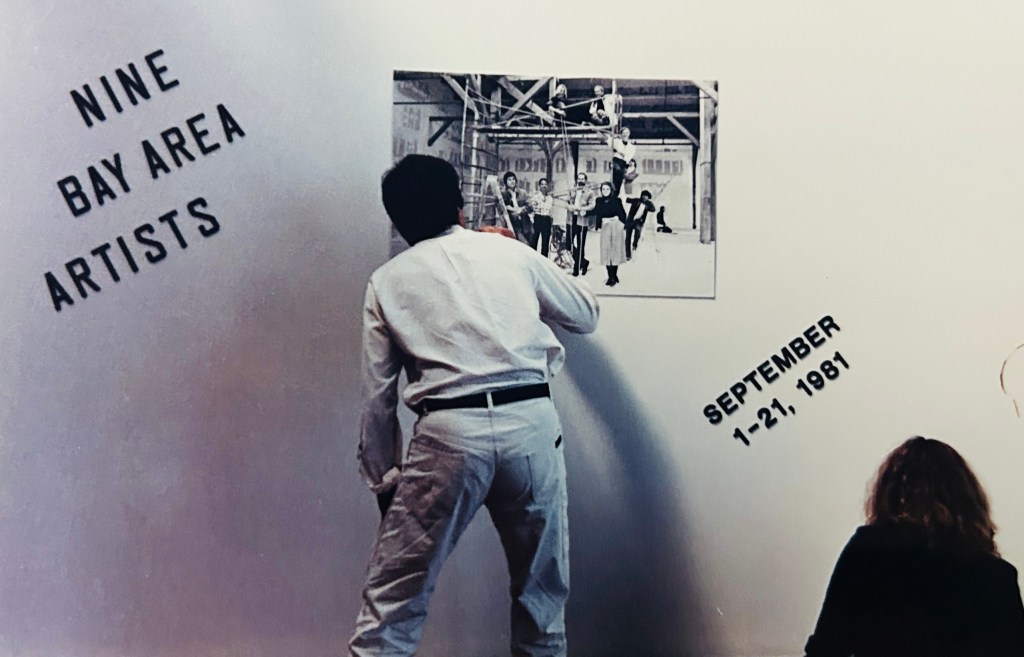

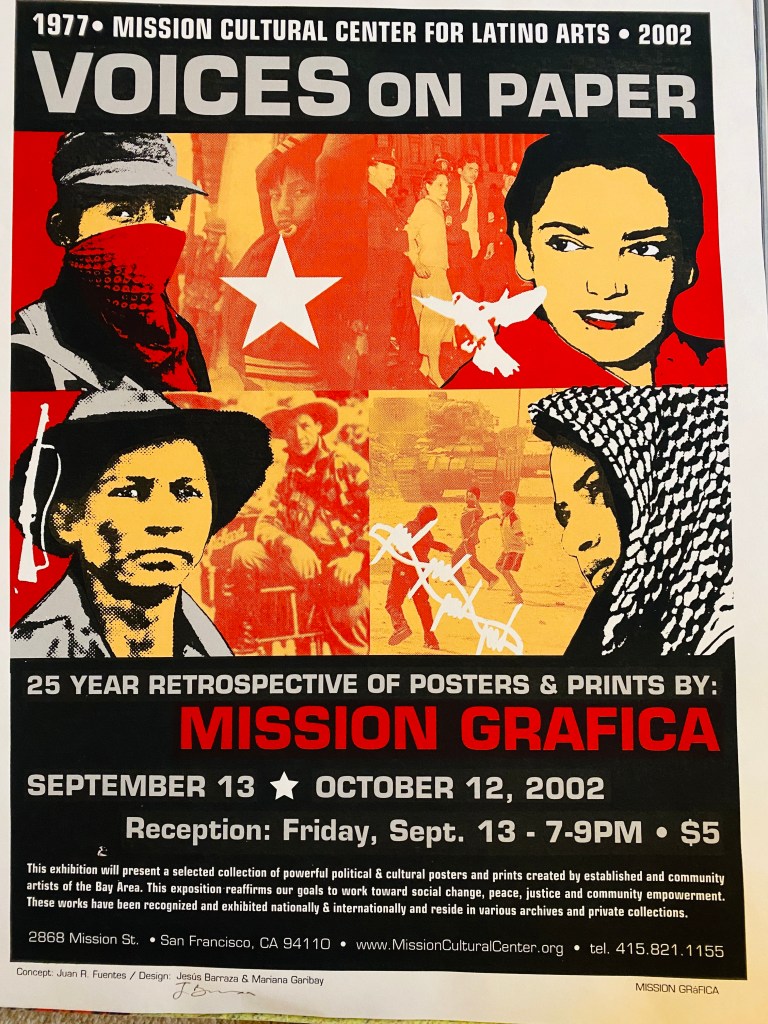

Art and Life in the 1980s: A San Francisco Gallery Experience

The time: Tuesday, September 1, 1981. Late afternoon.

The place: An art gallery in the South of Market neighborhood, San Francisco, California.

Some of the artists, dressed mostly in black, are huddled together, looking out a window. I can tell something is wrong. Wandering a little closer, I try to listen to their conversation while pretending I’m looking at a large blurry painting of a blue car (at least I think it’s a car).

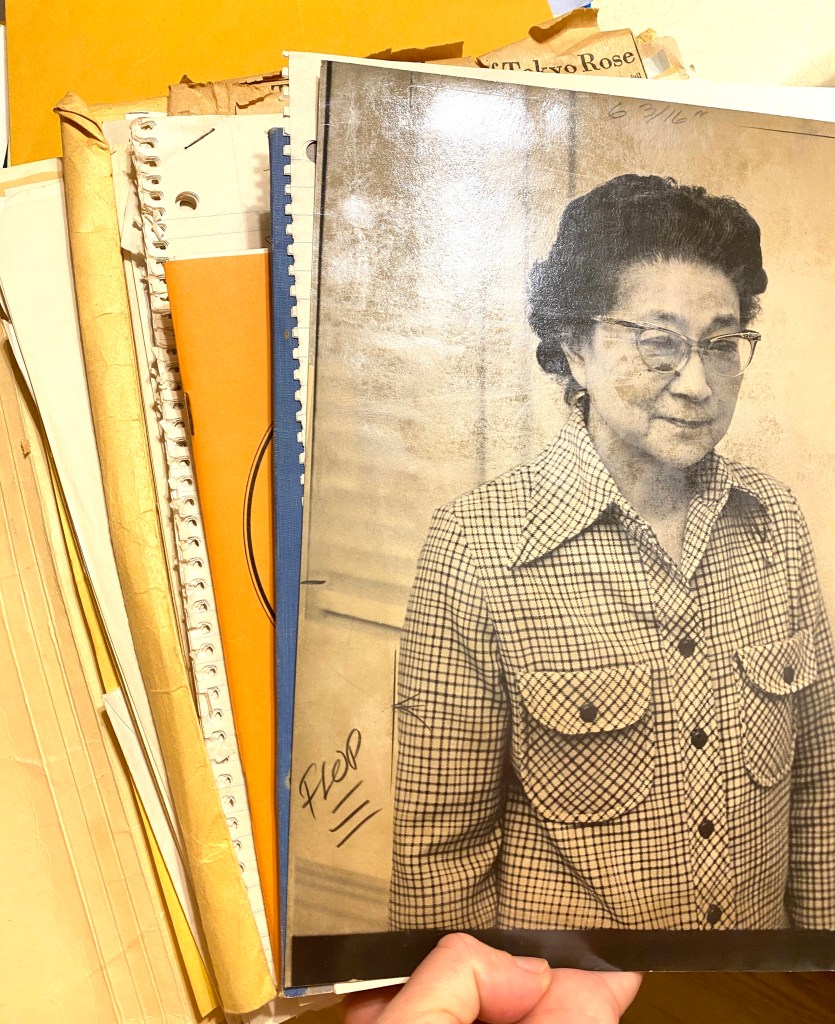

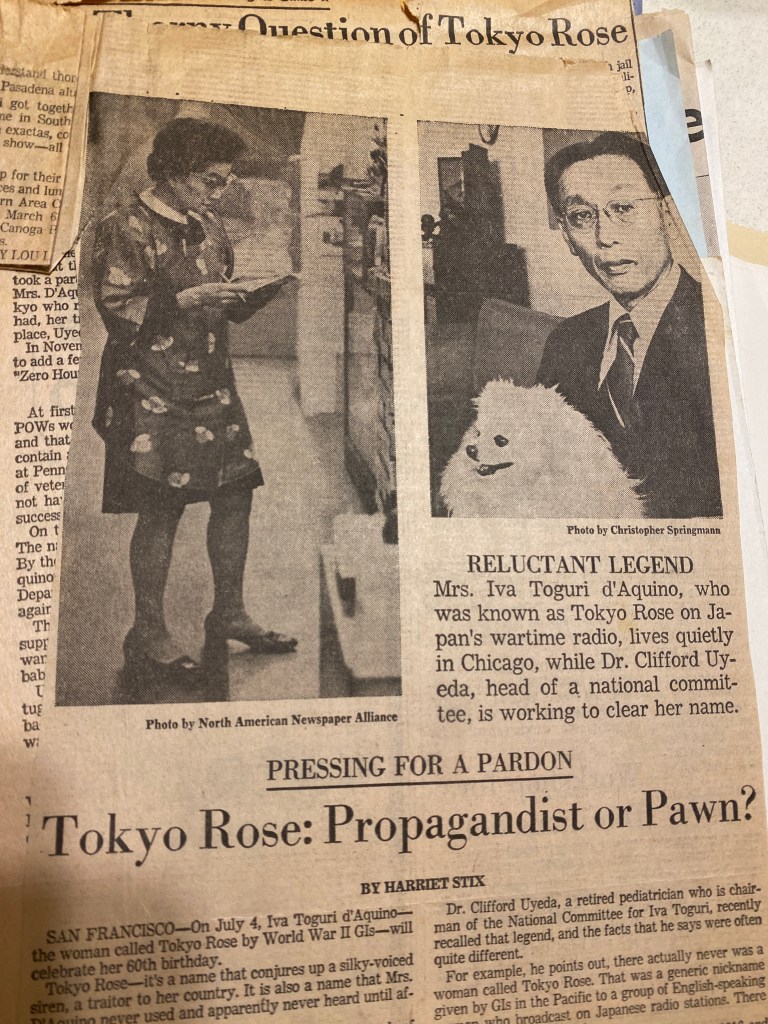

The nine artists featured in the show. “Look at him smoking pot out there on the street corner … he won’t come up here,” I hear Jill Coldiron say. “I mean, he doesn’t like his placement, but I don’t know why he’d sabotage himself this way during the reception.”

I head over to the food table to grab some more grapes and that yummy, crusty sourdough bread. I have no idea what Jill is talking about, but I do know that if anyone can solve a problem, she can.

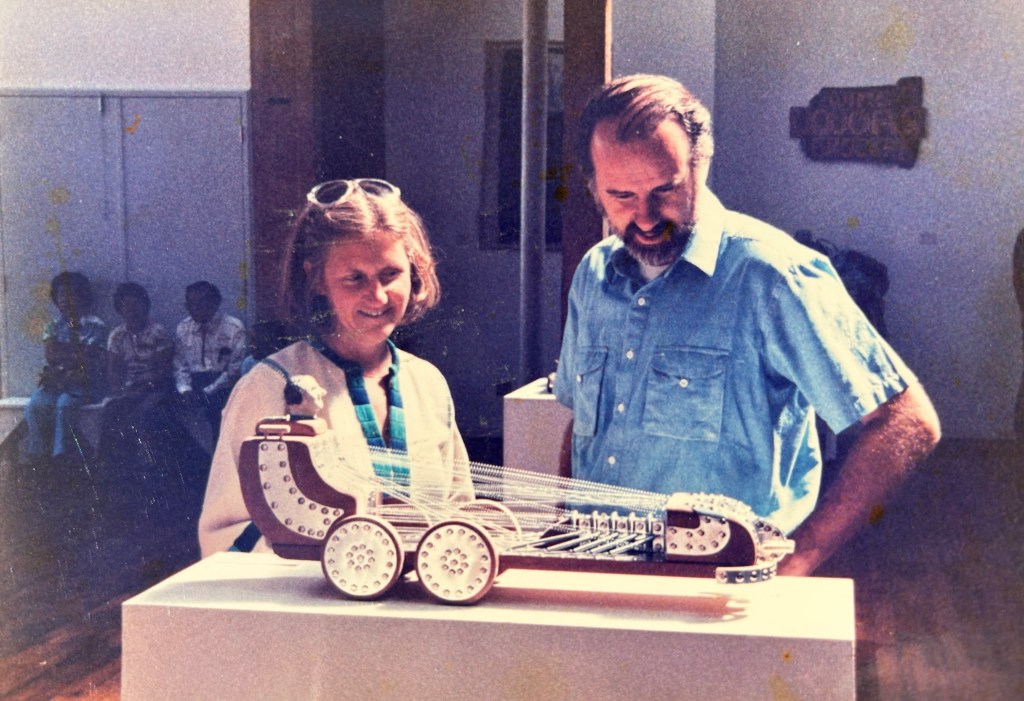

Jill is the organizer of this art opening and a good friend of my parents. I like being around her because she’s smart, loud, and funny. Sometimes my mom and I drive south across the Golden Gate Bridge and into San Francisco to have lunch downtown with Jill—I love doing that. She and my mom laugh so hard when they’re together it makes my ears ring. When Jill invited my dad to be in this group art show he yelled to my mom from the other room “Good news Patrish … Jill wants my cars in the San Francisco show!”

Curator Jill and my artist father discuss

arrangement of his cars in the show.The warehouse gallery is full of bright light, and the high ceiling is echoey with the sounds of clinking glass, people talking, and live music played by some nice musicians in the corner.

I’m the only ten-year-old here, something I’m pretty used to since I’m an only child. I don’t mind because I’m good at secretly spying on adults, just like Harriet the Spy.

Ten year-old art critic and part-time spy. Slightly wobbly in my wavy-soled high-heeled hand-me-down Famolare shoes and flowered Gunne Sax dress, I walk around looking for my parents. Spotting them across the gallery, I see that they’re standing next to one of my dad’s art cars. They look happy. That’s how they usually look.

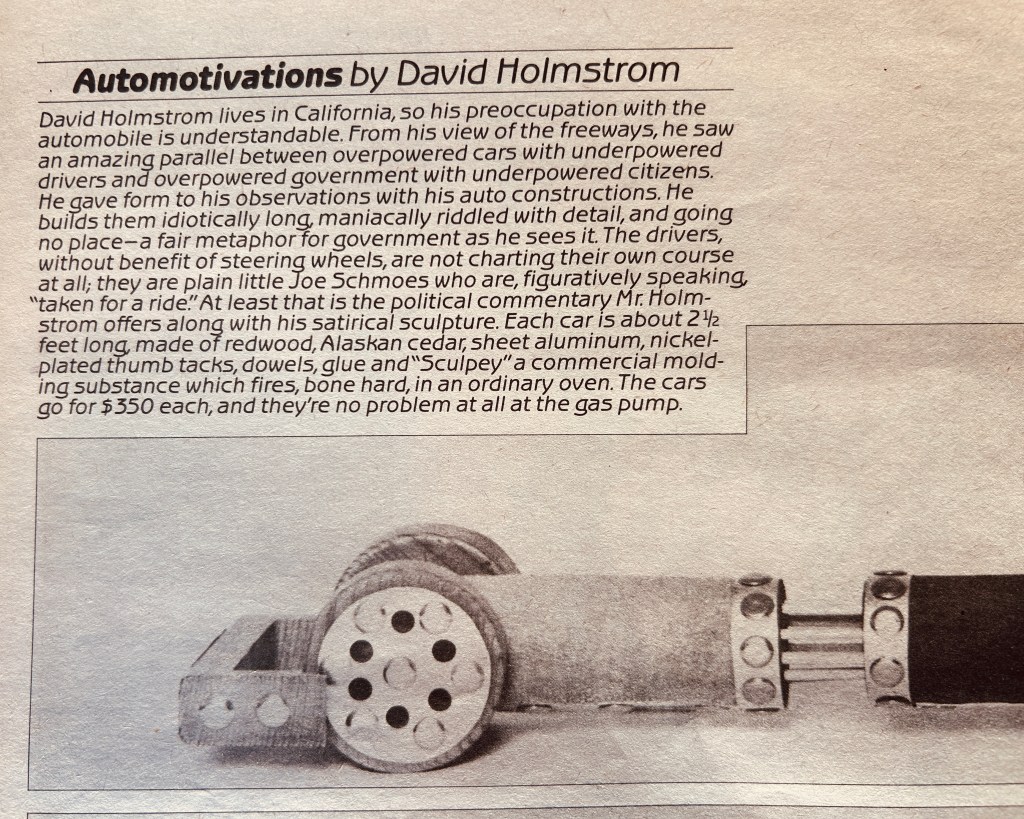

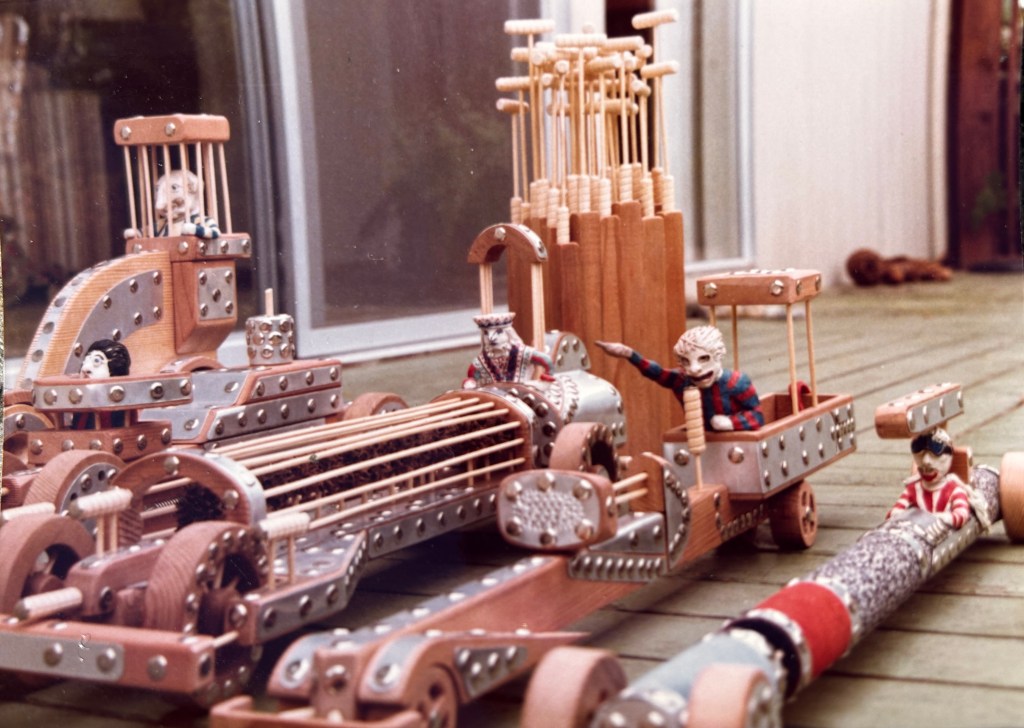

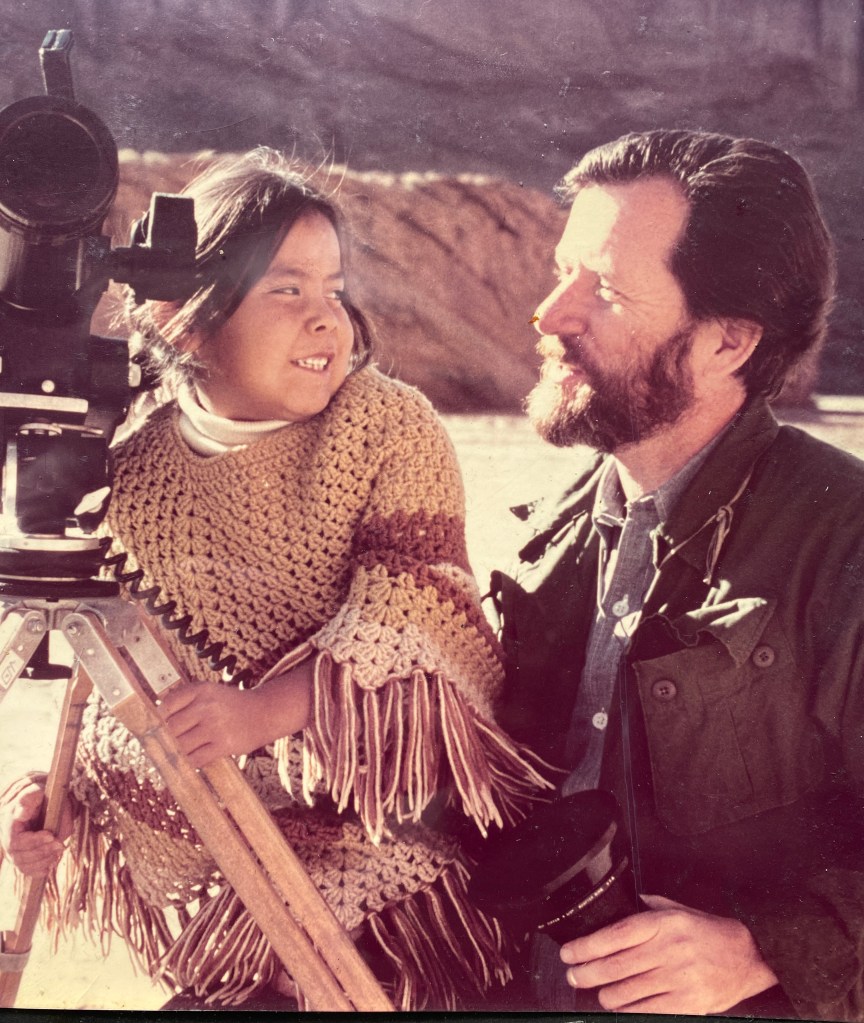

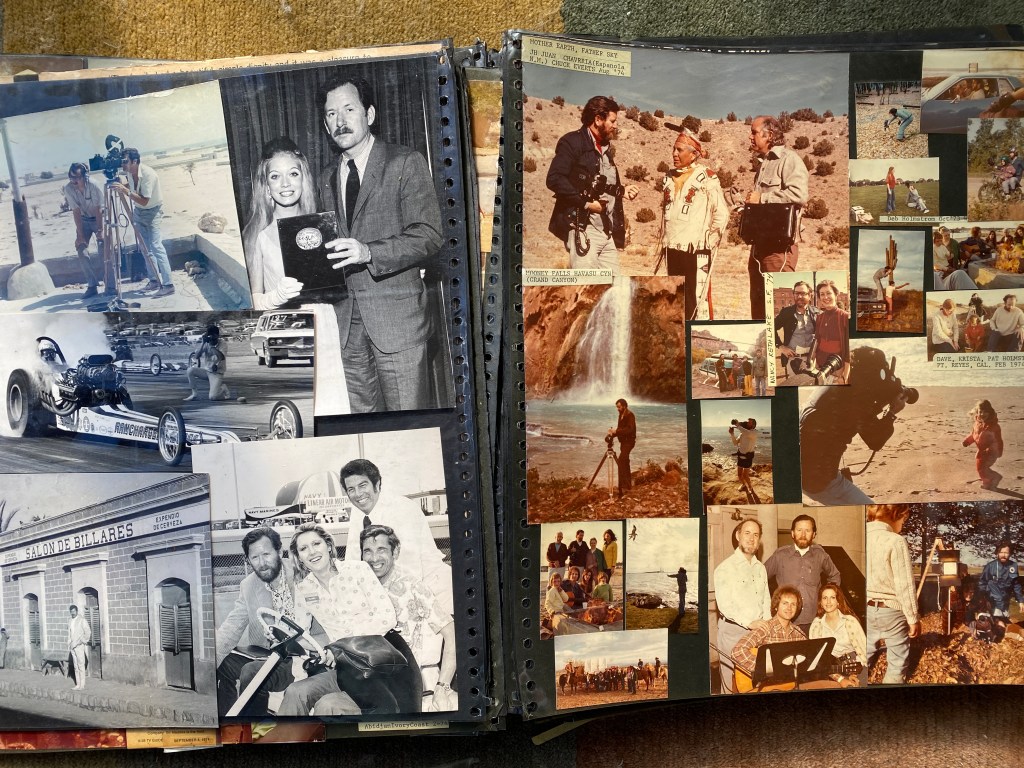

Mom and dad, artists and appreciators. Lately, when he’s not writing, my dad works on his cars. Most of his art, both the large wooden constructions, and the cars, make some sort of point about politics. I don’t understand the messages, but I like what he makes. A lot of other people seem to like his art too since there have been articles about him and his art in magazines and newspapers.

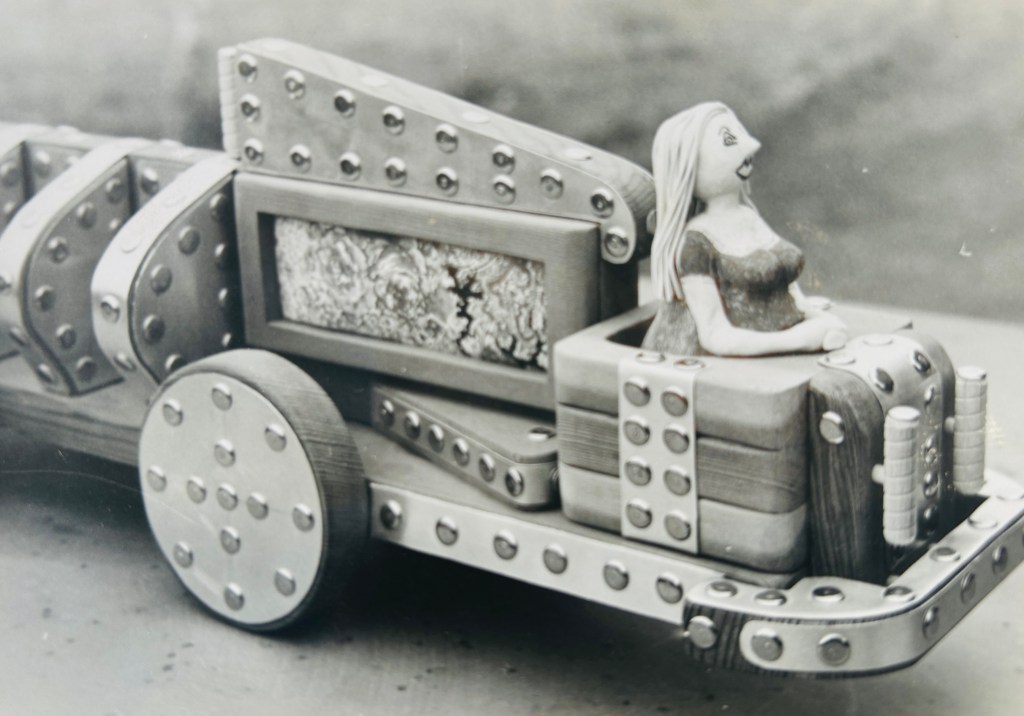

Excerpt from an article about my father’s art cars. The cars are shaped out of wood and have shiny parts made of sheets of aluminum that he hammers thumbtacks into. There are funny looking characters in the driver’s seat that he shapes out of clay. The cars have names I can’t pronounce, like Senator Kincade’s Private Secretary, Compulsory Arbitration, and The Subcommittee Investigator.

“The I.R.S.”

“Senator Kinkaid’s Private Secretary”

A selection of my father’s wooden art cars, circa 1983. I like it when my dad’s art is in shows, mostly because I get to spend extra time with him. Once he had his art in a street fair in Palo Alto and my cousin Laurel and I helped him set everything up. People stopped by and talked to us and bought some of his work. Normally, I’m not allowed to have sugar, but that day I got to have some cotton candy.

Supervising the Palo Alto street fair art booth with dad and cousin Laurel, 1978 We know a lot of artists. I like to make art too, but I don’t think I’m very good at it. My mom makes pottery on a big wheel that I can spin, and my best friend Portia’s parents are both silkscreen artists—when I sleep over at her house we sneak into their studios. We’ve seen stars through the skylights. We shake the brightly colored paint bottles and run soft paintbrushes across our cheeks. Sometimes Portia’s mom drives us to the art supply store in Santa Rosa in her tan VW bus. She lets us pick out pastels in colors we like.

When is this art opening going to end? My feet are getting tired, and my stomach hurts from eating all that fruit. The artist who was outside earlier is back inside the gallery now, talking to Jill in front of his sculpture that looks like huge melted Tinkertoys. His eyes are red and he still looks mad.

Now lots of people are gathered around my dad’s cars. A lady who is a friend of my parents commissioned (that’s a fancy word for “bought”) one of my dad’s cars for her husband. She’s giving it to him as a surprise. The musicians play a happy song while my dad announces that he made the car especially for the lady’s husband. There’s even a head that looks like his head driving the car. Everyone claps loudly. The man looks surprised and smiley, and his wife gives him a big kiss.

Unveiling of the art car commission. Time to ask mom and dad if we’re leaving soon. I’m too full of art and fruit.

I’m thinking about how art seems to make adults happy—when they’re making it and when they’re looking at art that other people made.

Except for that one artist, I guess.

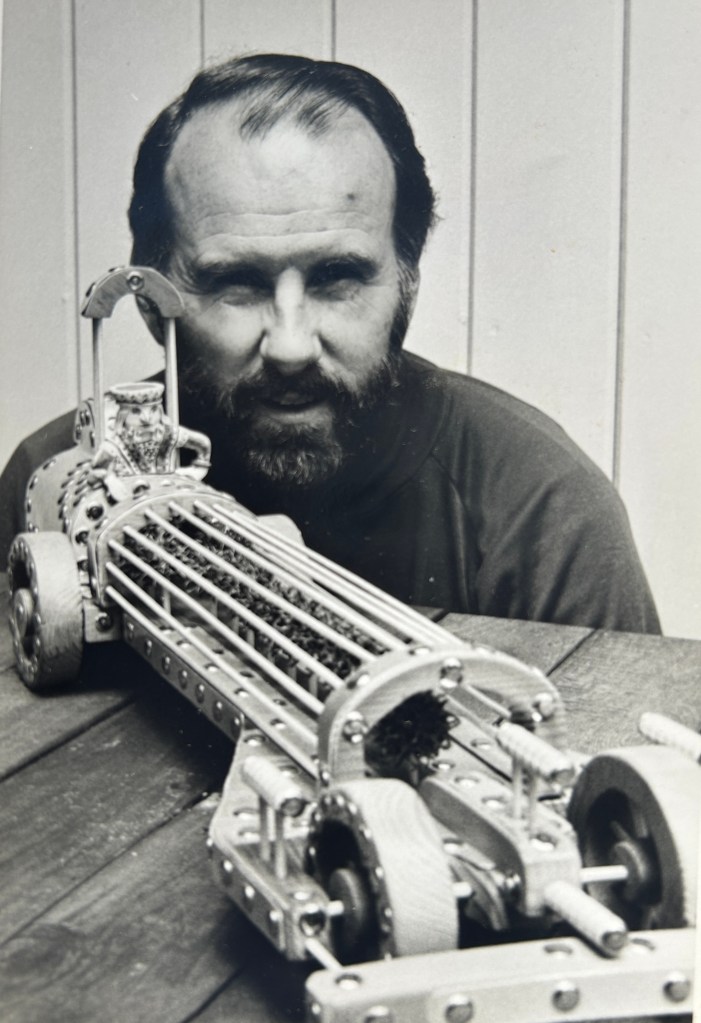

Artist David Holmstrom (aka my dad) poses

with one of his art cars. -

Catalina Dreaming

The town of Avalon as seen from Wrigley Rd. This is a story of dreams and reality colliding, in the best kind of way.

It is 7:30 AM Pacific and my husband and I are walking up a steep island road at a steady pace, breathing in the grassy scent of hillsides warming in the sun, the tropical foliage spilling into the road, and the sharply pungent Eucalyptus pods crushing beneath our feet. No one else seems to be around.

A few minutes earlier, we were tiptoeing around our dark hotel room searching for walking shoes and quietly moving stacks of clothing, damp bathing suits, and multiple pairs of Crocs. Our 11 and 12-year-old kids are still sound asleep, iPads and heads thrown to the side. Thanks to our wonky vacation schedule and a hefty time change, we have been granted an early morning reprieve from their boundless energies.

View from our Catalina hotel room patio,

Pacific Ocean in the distance.“How about walking up the road instead of down?” I suggest to Tom as we lock the hotel door behind us. He agrees, so we head right. Over the past two days of our visit to Southern California’s Santa Catalina Island, we have only exited our Spanish-style inn (on foot) and taken an immediate left. This move brings us down the steep road for the pleasing fifteen-minute walk leading to Avalon, the island’s main (and pretty much only) town. There are approximately 4,000 permanent residents on the 75-square-mile island, and almost all of them live in Avalon.

Welcome to the Island Valley of Avalon. “This place is like the best of California all rolled into one,” I marveled out loud as our ferry sailed smoothly into the Avalon harbor two days prior. The ravined mountainsides loomed in the distance, stunningly clear ocean water sparkled, and palm trees swayed. Was that the vanilla-like scent of plumeria blossoms in the air?

Bougainvillea and plumeria abound in Avalon.

As does water so clear you can see the bottom,

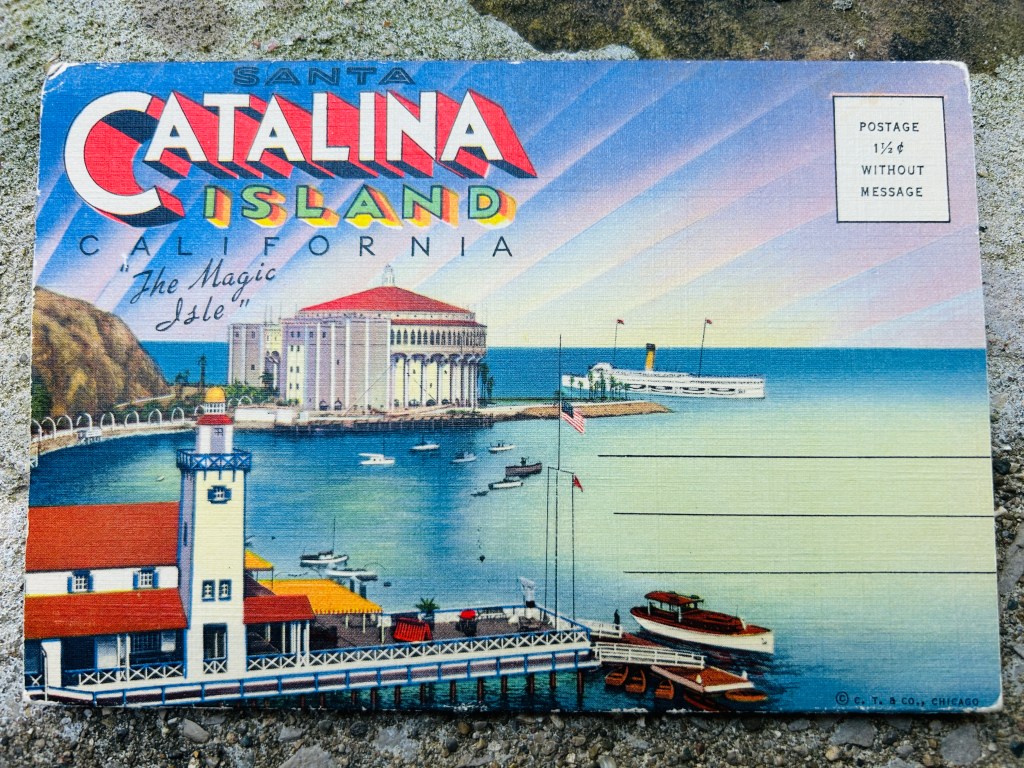

along with California’s state fish, the bright orange garibaldi.My father grew up in Los Angeles, and my paternal grandparents enjoyed their honeymoon on Catalina in 1929. I’ve been hearing about the island all my life. This, however, is my first visit.

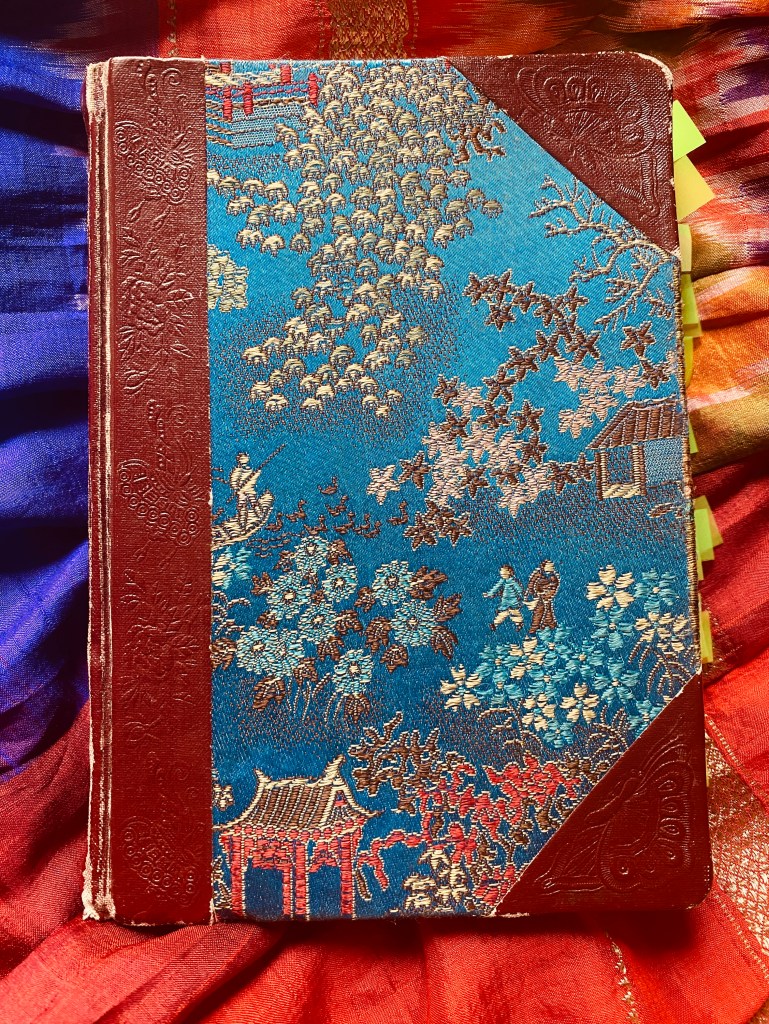

Postcard packet purchased by my paternal grandparents on Catalina Island

(never sent).So far, our family of four has investigated Catalina via golf cart, paddleboard, and foot, but we have yet to see what lies above our Spanish-style Catalina Canyon Inn, perched at the top of a steep canyon and topped off with a view of the deep blue Pacific beyond. I’ve been eyeing the Eucalyptus-lined curving road above the inn, hoping for a glimpse into the less touristy side of Catalina. As far as I can tell, there are zero hotels up there, only some quaint and funky-looking houses that I imagine are inhabited by locals.

Eucalyptus trees, a favorite since childhood. Catalina has some especially gigantic specimens. For me, this morning stroll is a slice of heaven. We had already been in California for a few days before journeying to Catalina. Experiencing Los Angeles with two preteens meant the itinerary looked a lot like their TikTok feeds: strolling the Santa Monica Pier, ogling the Hollywood Walk of Fame (featuring a flower-strewn star honoring the recently deceased Ozzy Osbourne), stops at Funko and Nike and LuLulemon, and an inaugural (for the kids) meal at the Eagle Rock In-N-Out.

But while we walked the crowded LA sidewalks, I found myself thinking about what was missing from this family adventure. As a native Californian who reluctantly left for the Midwest nearly 15 years ago, I am yearning for the California of my heart. The creative, kind, eccentric Californians that peopled my upbringing. The infinite, golden possibilities that lie around every corner. The bright orange of California poppies lining dusty roadsides, the sight of a graceful lone oak perched on the top of an emerald mountain in the springtime. This California lives on in my dreams, but these days, news stories paint lurid pictures. And as I lead an entirely different life 2,250 miles away, I wonder if the soul of that California still exists.

Idyllic Catalina view. Reaching the top of what I am now calling “Eucalyptus Road,” we follow a hairpin curve and find ourselves on an upper stretch lined by houses on each side. The structures remind me of parts of Northern California towns Berkeley or Mill Valley, narrow wooden constructions, close together and very, very steep.

Suddenly, a man and his dog appear in front of us. Smiling broadly, the man greets us, as does his friendly, tail-wagging pup. “Nice morning, isn’t it? Have you had your coffee yet … just put a pot on … can I offer you some … my house is just up here.”

It might have been the perceived safety of an island, or the idyllic early morning atmosphere, but there are times when you sense that a human being you are meeting for the first time is a good one. This is one of those times. Nodding in unison, we accept the stranger’s offer without hesitation.

Some have maples in their front yard, others have

this glorious flowering marvel.Minutes later, we are trudging up the steep wooden stairs to the main floor of our new friend Bob’s house. There, in his elegant, sun-splashed kitchen/dining room, which smells of cinnamon and flowers, he hands us each a mug of strong coffee. We sip, admiring our surroundings, chatting about the artwork adorning the walls. Bob then proceeds to give us a tour of his lovely home, combined with a fascinating people’s history-style lesson about the island (for example, many islanders apparently believe actress Natalie Wood’s 1981 drowning in the Catalina harbor was an accident afterall, thanks to copious amounts of alcohol consumed that night).

At one point in the tour, I stand on Bob’s third-floor open-air pillow-strewn sleeping porch, looking down at the crescent moon town of Avalon, which is exquisitely framed by the blue expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

A shiver goes through me. “It’s still here,” I think to myself. The California of my dreams.

Hidden sunburst along a Catalina sidewalk. Turns out, Bob is a retired bond trader turned poet. Of course he is.

And in his creaky wood-floored, weathered office, sailing ships adorning the walls, he reads us a poem. Closing my eyes, I allow his words to wind their way through me.

To change one’s mind/To open one’s heart—/One leaves the known behind

To take a different path/Than the one well-worn,/Opens the world /And opens the soul

Excerpt from “Pilgrims,” Songs of Redemption Poems by Bob Baggott www.offtheDesk.com

Walking California’s paths … into the future. The soul of California hasn’t gone anywhere.

And sometimes, when you least expect it, you are reminded that infinite possibilities still exist.

-

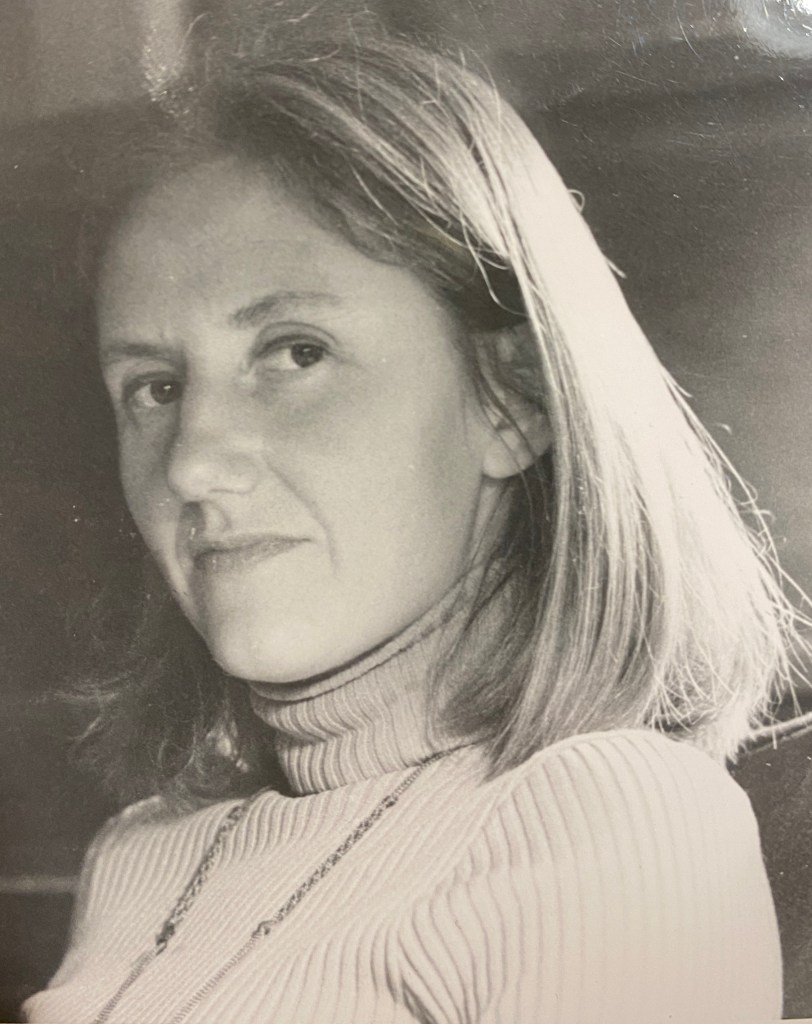

The Missing Mom Muscle

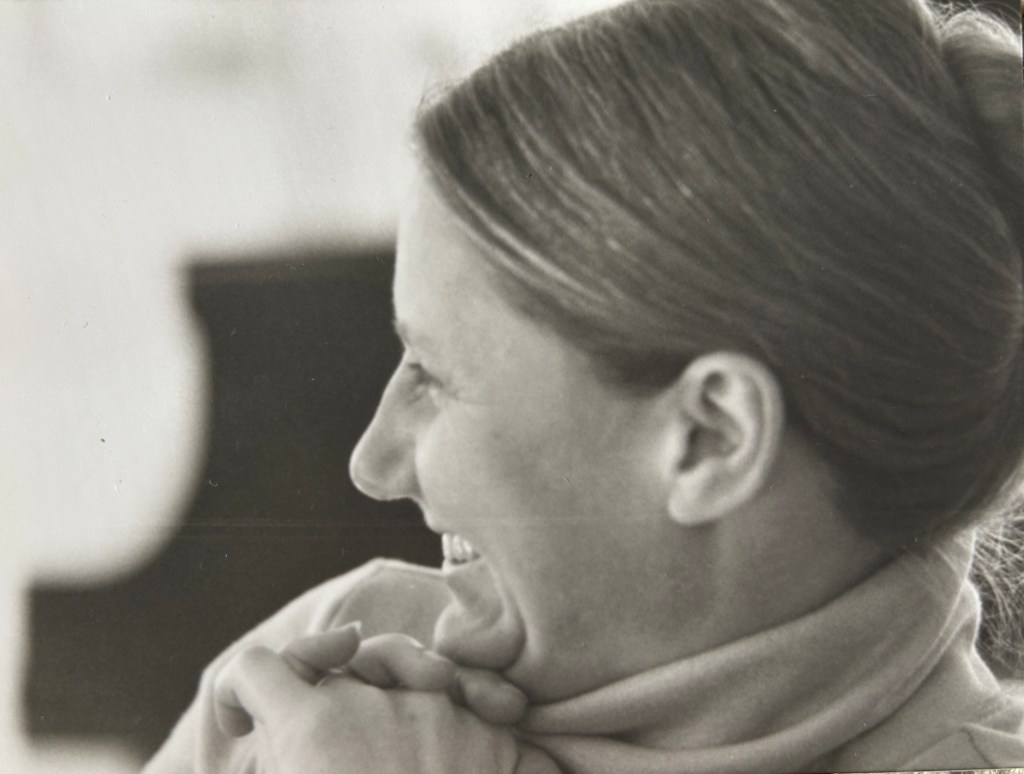

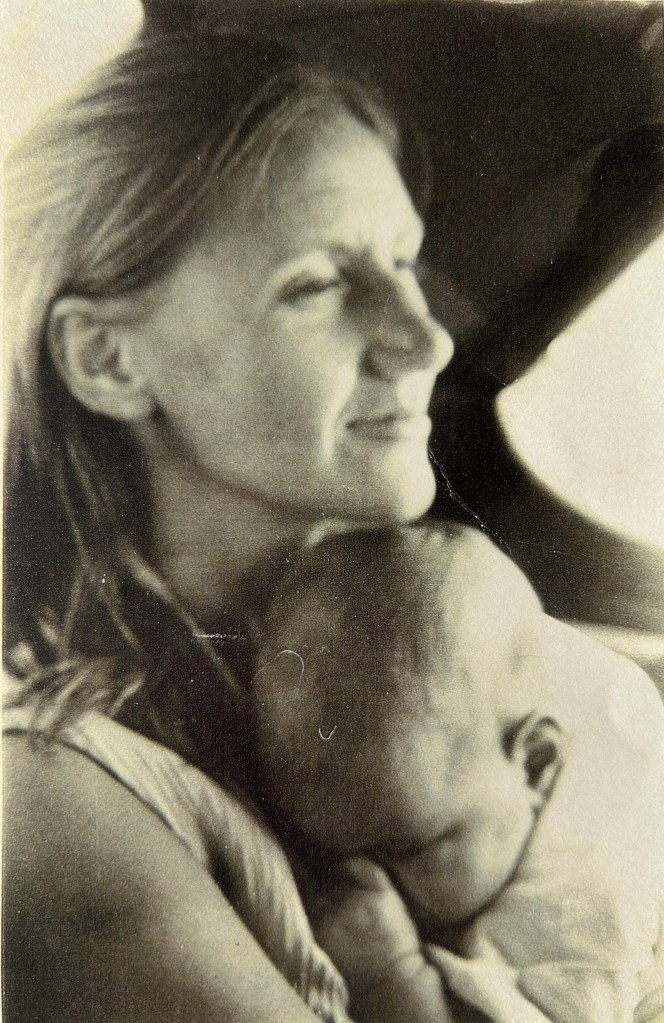

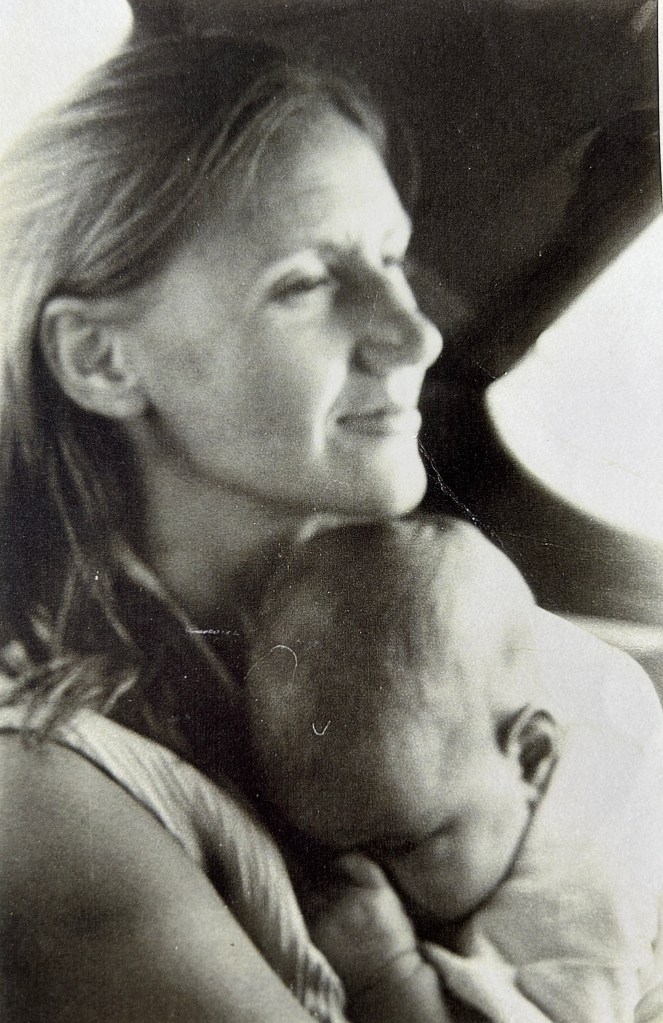

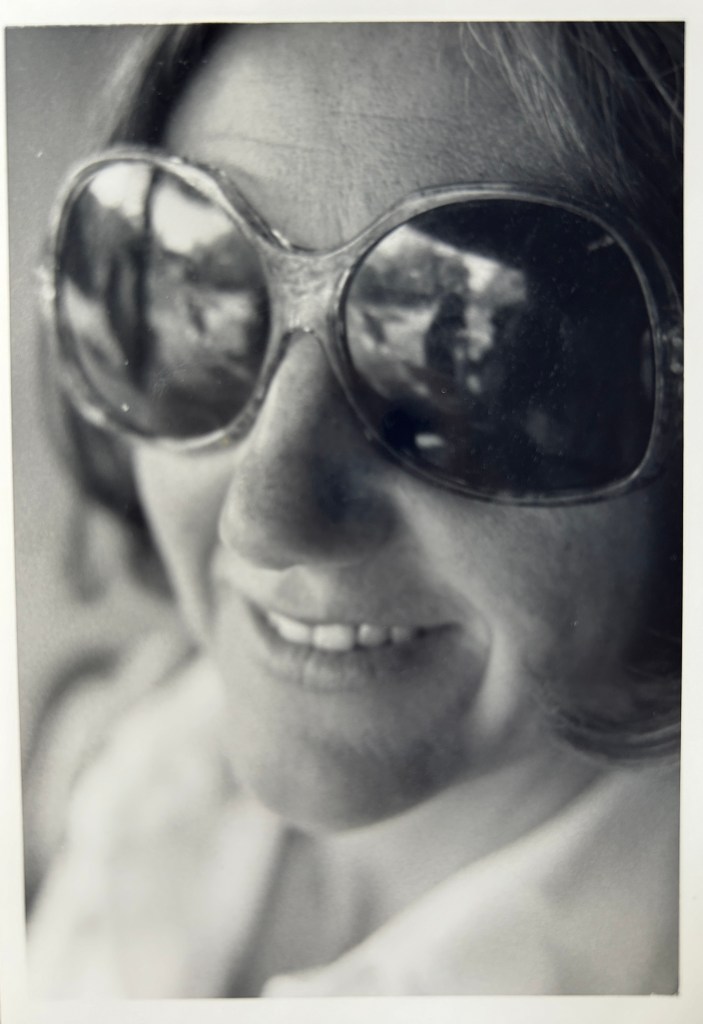

My Mom and her smile, 1975 When your mom has been gone for 23 years, you develop a muscle. This missing mom muscle strengthens each time you use it, keeping you afloat when you might otherwise drown in her absence.

You flex the muscle when you want to call her, but she’s not even in your contacts—she died before the first iPhone. When you see her favorite Constant Comment tea at the grocery store. When you find the wrinkled brown paper bag holding her gold-rimmed China plates. When you smell the bittersweet scent of marigolds, or her soft lavender-colored wool sweater you keep on the top shelf of your closet. When you hear Robert Redford died—she adored him, especially in The Way We Were.

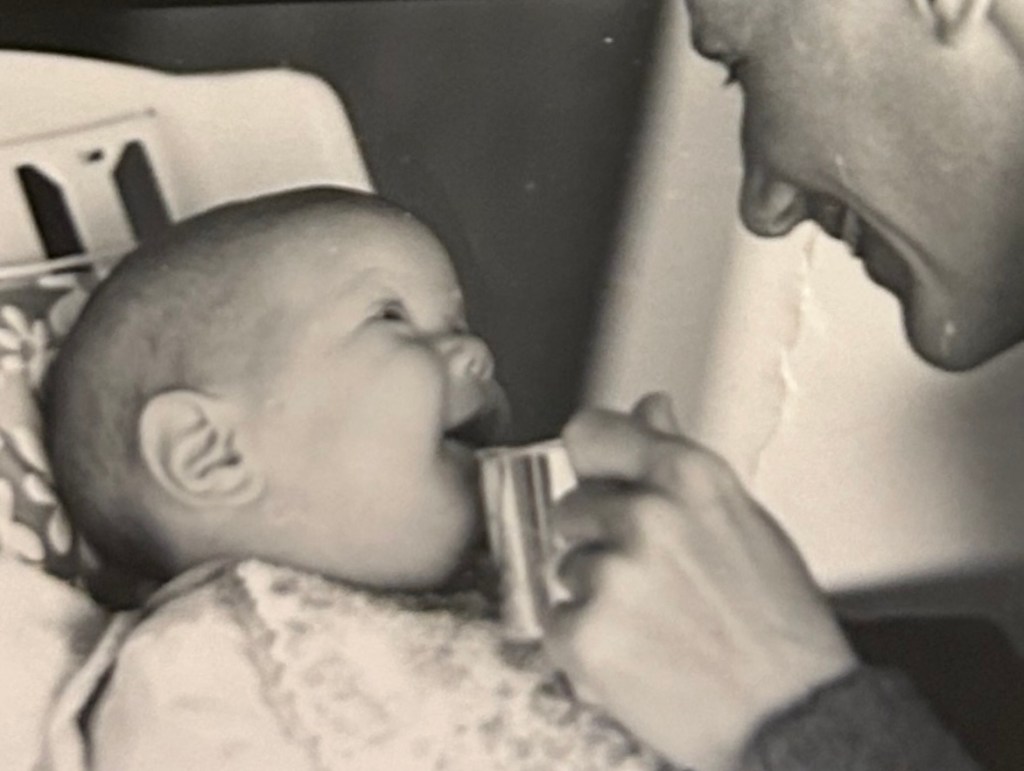

The safest place on earth (backseat of a

Volkswagon Beetle), 1971Watching your Kindergarten students love their mothers, your missing mom muscle twinges. Every morning, a little girl tells you her crayon picture is for her mama. Rainbows, crooked flowers, lopsided smileys, and dark caves—each one for mama. A lump forms in your throat, but you flex the missing mom muscle and push it down. You want to tell her you understand, that all you do is for your mom too, but you don’t think that would make sense to a five-year-old (although you might be wrong). Instead, you smile, praise her picture, and say you know her mom will love it.

Kindergarten masterpiece, for her Mama The times that are the hardest, the times when the missing mom muscle gets a serious workout, are when you feel mistreated or misunderstood. Even, maybe especially, by your own family. Those are the times when you want to collapse into her arms, to feel her cool hand on your forehead, to hear her softly singing hymns to you like she did when you were a child. Mostly, you want to be understood the way she understood you, to be known and loved the way she knew and loved you. You hate the devastating truth lurking behind your yearning—no one will ever understand, know, or love you that way again.

In those times, the missing mom muscle feels like it’s tearing.

Other times, you want her to swim in your puddle of pride. The change in careers, the longevity of your marriage, your spiritual evolution, the birth of your children, your writing, and your sobriety. Your triumphs would be that much sweeter if she knew, if she could celebrate alongside you.

Enjoying Mexico with Mom, 1998 You sort through pictures, and you find some of her gazing at babies.

One of the babies is you.

You know she would have looked at your children, her grandchildren, the same way, and that they would have adored her. You know she would have loved them the way she loved you. You feel as if there is a gaping hole in your children’s lives, and you wonder if they feel it too.

You close your eyes and call on all she taught you about the power and the infinitude of Love. You flex the muscle harder than ever. These 23 years have taught you that you won’t, you can’t, let yourself drown without her.

You keep going.

-

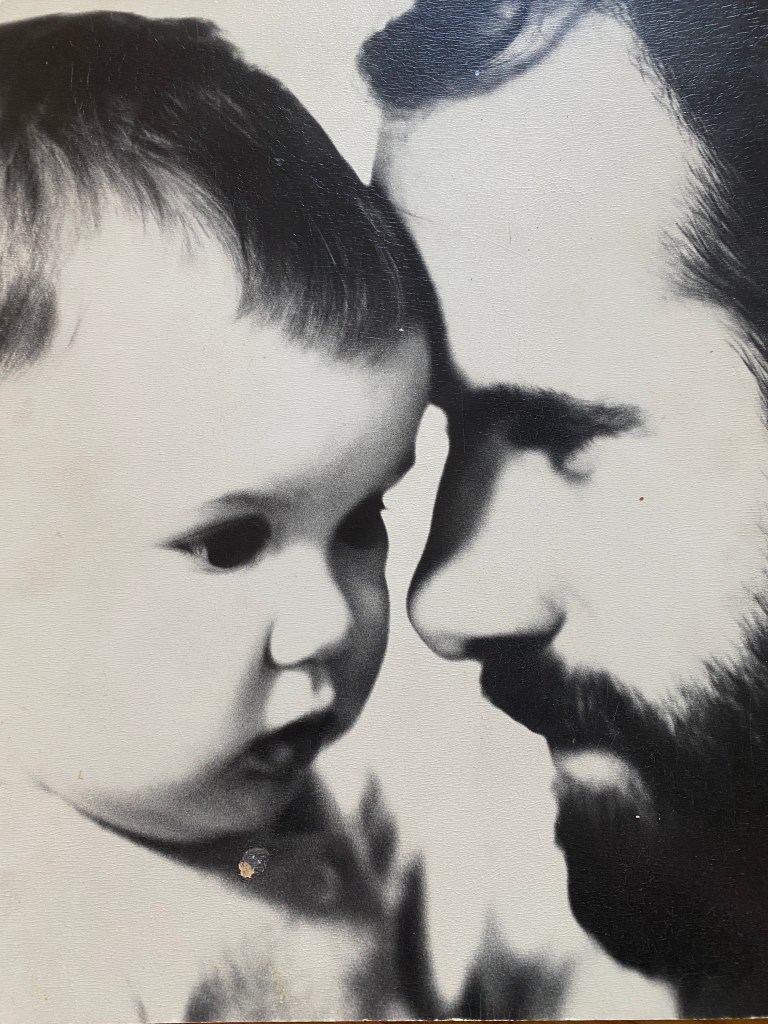

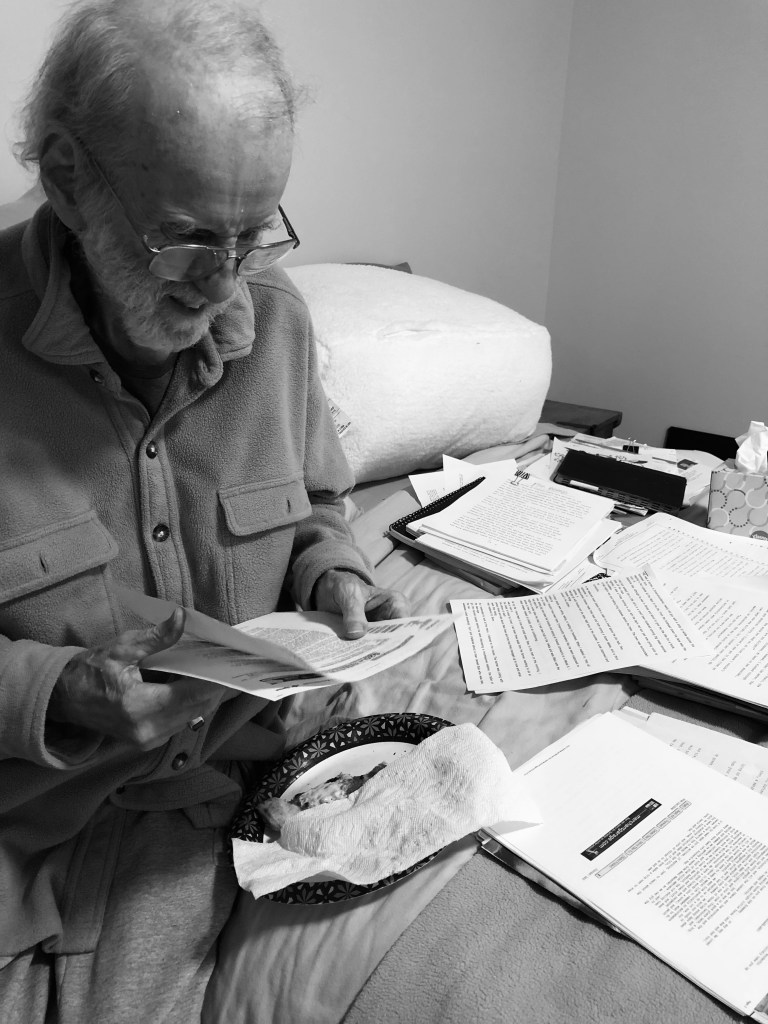

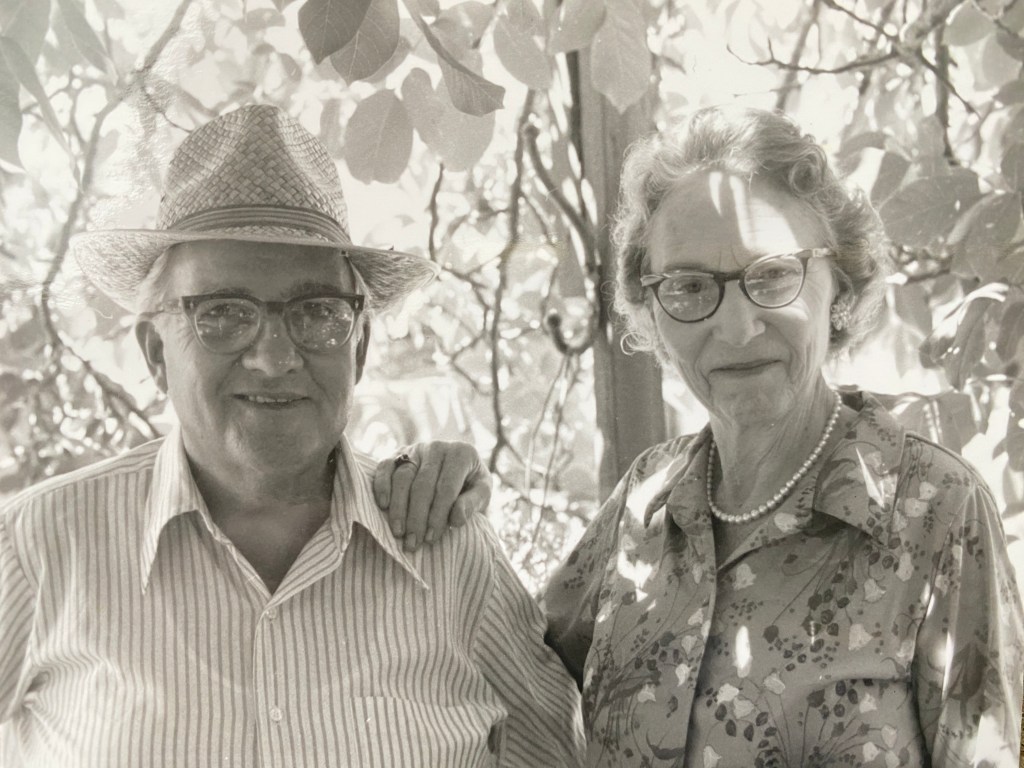

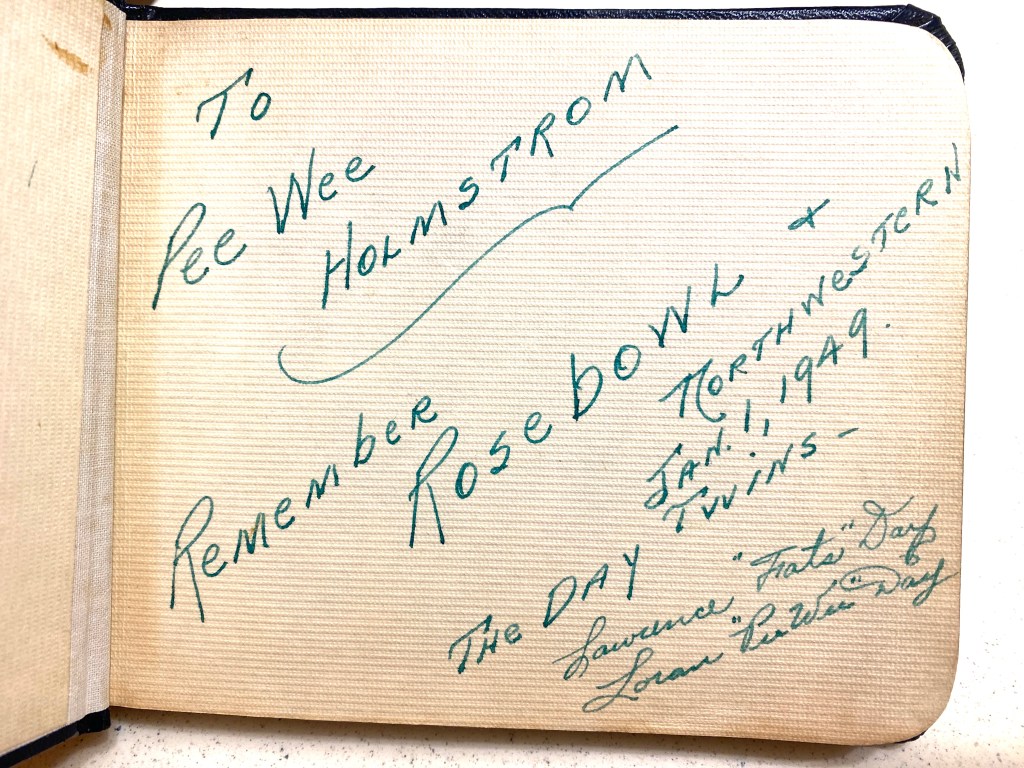

Integrity and Friendship: A Tale of Two Fathers

The fateful meeting, late summer 2004. Years ago, two men of integrity walked down a San Francisco sidewalk.

Heading to the Saturday Farmer’s Market in the Ferry building, they made a striking pair. One was tall and lanky with long loping strides, the other short of stature with a quick shuffling gait. The shorter man took two steps for every one the tall man took. On that chilly, foggy Saturday (it was summer in San Francisco, after all), as they strolled along they exchanged ideas about basketball and politics and UCLA (which they had both attend/and or worked for), and the state of the world in 2004.

The daughter of the tall man was dating the son of the shorter man. The men had known each other less than 24 hours, having met the night before at a table tucked into the back of a crowded seafood restaurant on Polk Street. A gigantic bottle of Veve Clicquot champagne sat chilling on the table, a surprise gift provided by one of their children’s high-powered bosses to mark the occasion – two families connecting for the first time.

The introduction of these two men was significant not only for their son and daughter (who would go on to marry and raise future grandchildren who the two men cherished) but for another important reason. The tall man and the short man were each exceptional in character, in achievement, and most of all, in their roles as world-class reliable, loving fathers.

It didn’t matter that one of the men believed in God and the other in classical music. That one preferred apple juice, the other vermouth. That one had an absent father, the other a present one. Instead, they leaned on their commonalities— a passion for books, baseball, basketball, and travel ran hot through their collective veins. Both had backpacked through Europe in their early 20s and burned through every last dollar. The two men also shared an ability to view life through a global lens, lifting up the people working toward active peace and reconciliation and calling to task those who stirred war and destruction. Successful careers had challenged and fulfilled them—the tall man as an award-winning writer/journalist and the other a respected professor/Dean at a Big Ten university.

Unlike so many men of their generation (born in the late 1930s), they viewed women not only as equals but as individuals to be championed, as co-workers to support and mentor. Both had chosen remarkable women as partners to whom they remained committed and loyal for as long as they were able (the tall man’s wife had recently died when the men first met). In fact, one of the reasons the tall man’s daughter knew the shorter man’s son was a keeper was that she noticed the son enjoyed close, easy, respectful friendships with women. She has no doubt he learned from his father’s example.

Soon after, the shorter man’s son and the taller man’s daughter eloped to San Francisco City Hall (the families managed not to hold it against their children). A year later, the son and daughter left San Francisco for the Midwest. They settled down the street from the son’s family, including the shorter man of integrity. Soon after, grandchildren joined the family, which thrilled the two fathers—now grandfathers—to no end.

At family gatherings and holidays, the short man and the tall man enjoyed each other’s company, discussing grandchildren and books, movies, and traveling. The tall man, who lived in another city, visited often. The two men adopted the Spanish noun “consuegro” (meaning in-law) to describe their relationship. “Ahoy, Consuegro!” they would say loudly as they thumped each other on the back. To them, the foreign term legitimized and solidified their familial friendship.

One tall, one short. Both impressive. Despite their stellar qualities, I do not mean to imply that these were flawless men. In fact, challenges hunted them throughout their lives. The short man was born prematurely, his tiny body cradled for weeks in a hospital without air conditioning. In his early years, the tall man was plagued by a severe stutter. In childhood, both men were taunted for their differences. Later on, there were tyrannical bosses, an early divorce, a tendency for one of them to drink too much. Yet during their formative years, neither man became bitter or angry and avoided blaming others for their problems. They remained caring and open to the world. They consciously decided to learn from their mistakes and avoid harnessing anger in destructive ways or using loved ones to deflect and/or pay for the sins of others.

In 2020, the pandemic hit, along with stormy seas for the two men of integrity. The shorter man, having been felled by a massive stroke on Christmas Eve 2019, found himself in a Midwest rehab center no longer able to walk, or even read. There were few visitors, and for the first time in decades, the subscription to his beloved New York Times (a daily fixture of his pre-stroke life) had to be canceled.

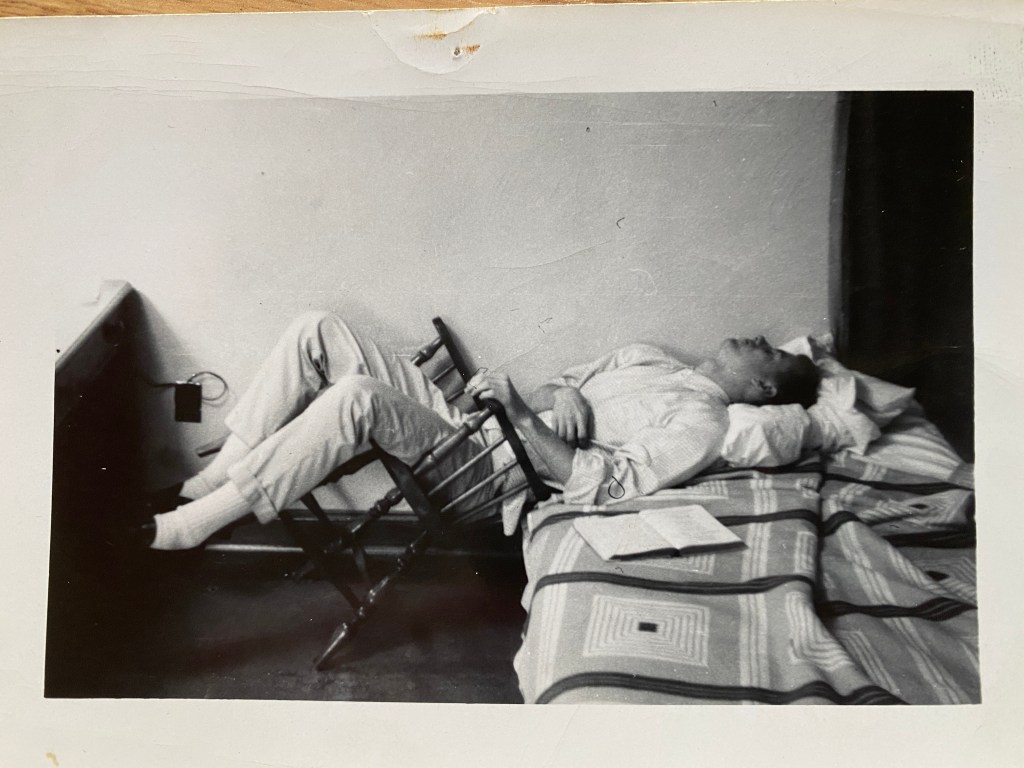

The taller man, facing dual dementia and lymphoma diagnosis, had recently been moved by his daughter to the same Midwest town where she lived with her family, just down the road from her in-laws. Incredibly, the daughter found an apartment for her tall father in the same retirement community where his shorter consuegro was undergoing rehab for his stroke. The tall man, thanks to worsening dementia, was no longer able to spend his days writing and could now be found at the small library in the retirement home reading his beloved New York Times (often the same paragraphs over and over).

Despite their failing health, the two men of integrity were able to attend a few of their grandson’s baseball games where they sat, socially distanced from each other, watching the action and shaking their heads in collective amazement at the eight-year-old’s impressive pitching skills.

Enjoying the local ballpark with their grandkids. Back at the retirement community, the tall man discovered that he could walk to the shorter man’s room in the rehab building and began to make his way there for daily visits. Seventeen years after their first sidewalk stroll, neither man could have imagined that this is where they would end up: sharing the same retirement home, in failing health, during a pandemic. Health issues were piling up like rush hour traffic in Los Angeles and both men struggled to accept that they had entered their final chapter(s). Yet, alongside the struggle, their friendship burned bright. During those historically difficult months, while pandemic chaos raged around them, they sat, masked and happy, discussing basketball and baseball and exchanging ideas about the Midwest, politics, and the state of the world in 2020.

We live in a world desperate for men who lead with integrity, and who contribute through their intellect, not just their muscles. Men who are generous with their talents and lead with open hearts. Who can drive when required, but refuse to steer their own ego’s bus into a crowd of innocent bystanders, forever tainting lives. Men whose loyalty to their spouses and those they love is paramount. Men who champion and mentor women in the workplace, and in academia. Who refuse to look at women through the limited lens of sexuality and don’t allow what is between their legs to lead their lives. We need men who are curious about the way the world works, and who want to make this planet a better functioning place for all of us.

Sadly, both men are gone now. The tall man died in 2020. The shorter man passed a month and a half ago. In life, few things matter more than integrity and friendship and these two perfected both. May the children and grandchildren of the two men wrap their legacies across our shoulders like a warm blanket and draw from what they poured into us for the rest of our lives.

Once, at a party celebrating the shorter man’s 8oth birthday a family friend who happened to own a classic blue Thunderbird convertible nudged the two men and remarked, “You’re only going to be 80 once, why don’t you take it for a drive?” Needing no other encouragement, the two jumped in. Quickly fastening their seatbelts, they grinned at each other and then took off into the sunset, waving all the way.

Taking the wheel of the Thunderbird. The tall man of integrity was David W. Holmstrom and the shorter man of integrity was Richard E. Stryker.

Oh, how we will miss them both.

-

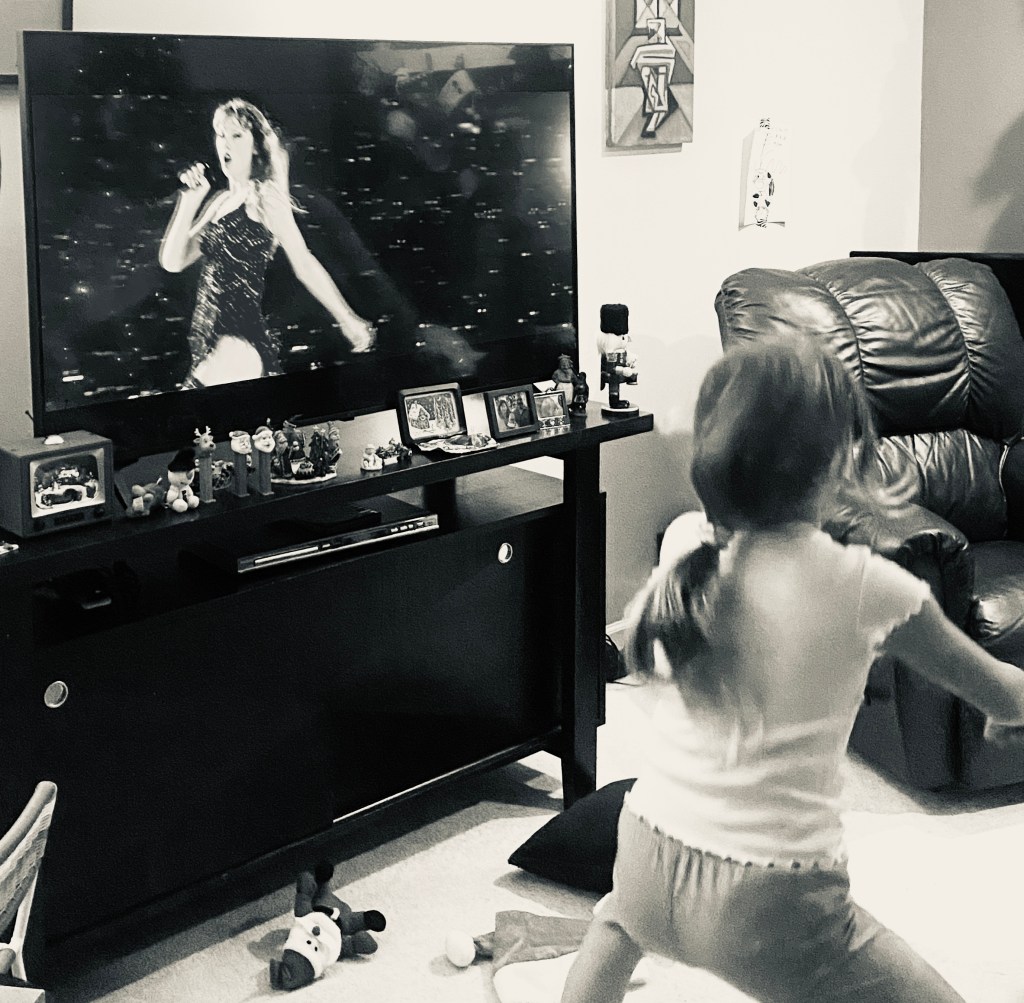

Picturing Love and Laughter

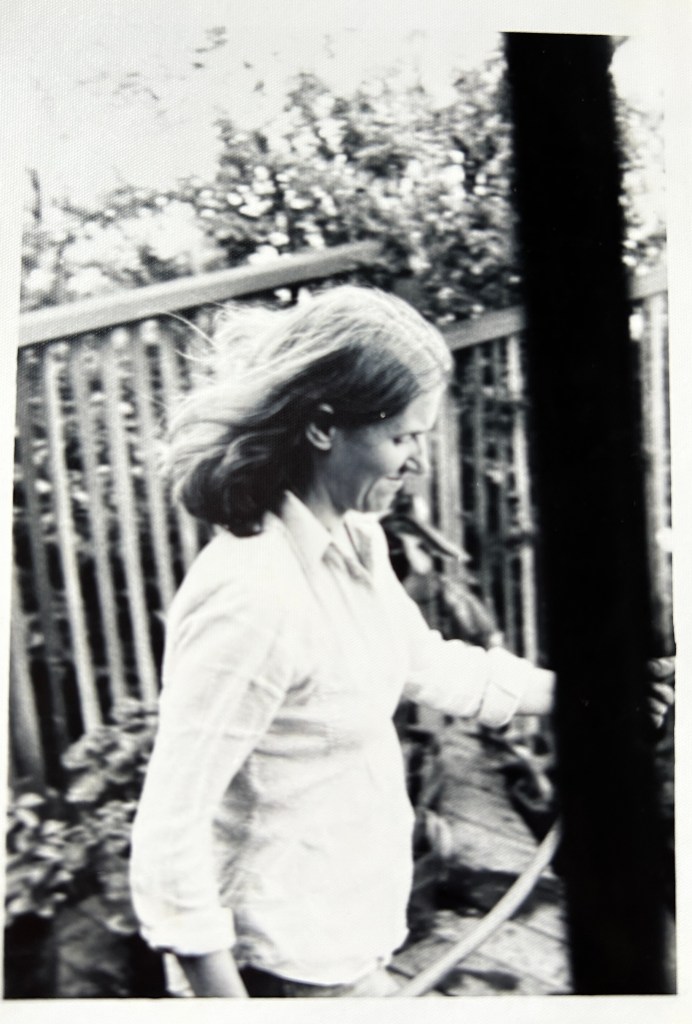

Massachusetts, 1970 Today, in honor of my mother’s birthday, I will share a hot tip: find a partner who sees and admires you enough to take pictures of you as beautiful as the ones my father took of my mother.

San Francisco, California, 1971 My mother, Patricia H., was an East Coast native who took to Northern California and its terrain and culture like a cat to a warm shaft of sunlight. She stayed for nearly two decades, living and loving. Besides her work as a spiritual healer, she counted caring for me and my dad and tending a large abundant organic Sonoma County garden (that fed our family of three for years) as her greatest joys.

Yosemite, California 1974 A woman both vibrant and quietly confident, her boisterous grinning laugh used to take over her body while her head bobbed slightly to the infectious beat. She affectionately called me Chickadee and to me, her only child, time seemed to pause while I took in the beauty of her laugh.

Honolulu, Hawaii, 1969 A memory of her laughing will remain forever in my mind’s eye, but I also like to keep a photo of her in the act above my writing desk. In the image, taken by my father, my mother and I enjoy a humorous moment at my fourth birthday party.

Cocoa Beach, Florida, 1975 Unbelievably, my mother has been gone for nearly twenty-one years now. Thankfully, photographs play a vital role in keeping her image alive. My children never had a chance to meet their maternal grandmother but I hope that they can gaze at her photographs (and some video) and imagine her as part of their experience.

1979 Because she still is.

Larkspur, California 1977 My mother’s career as a spiritual healer meant she helped people learn about divine Love. She had a gift for facilitating trust and understanding that resulted in true healing. I often think about how the world could really use her prayers right about now, but I also believe she is still actively sending them our way.

Heidelberg, Germany, 1991 Happy Birthday to you, mama. Keep laughing.

1998 -

Swimming Through Life with Phish

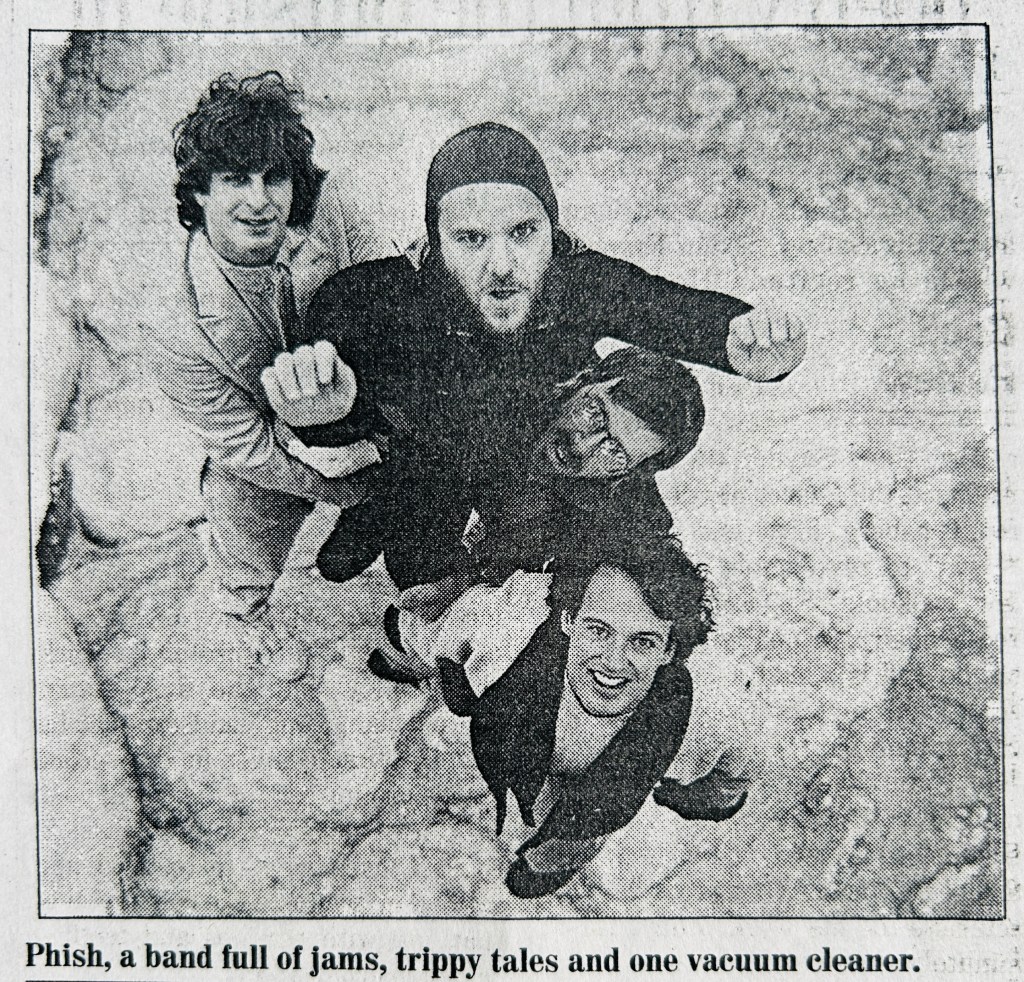

Phish, pictured in The Boston Globe, January 2, 1993 “When I jumped off, I had a bucket full of thoughts

When I first jumped off, I held that bucket in my hand

Ideas that would take me all around the world”

-Phish, Back on the Train, Farmhouse

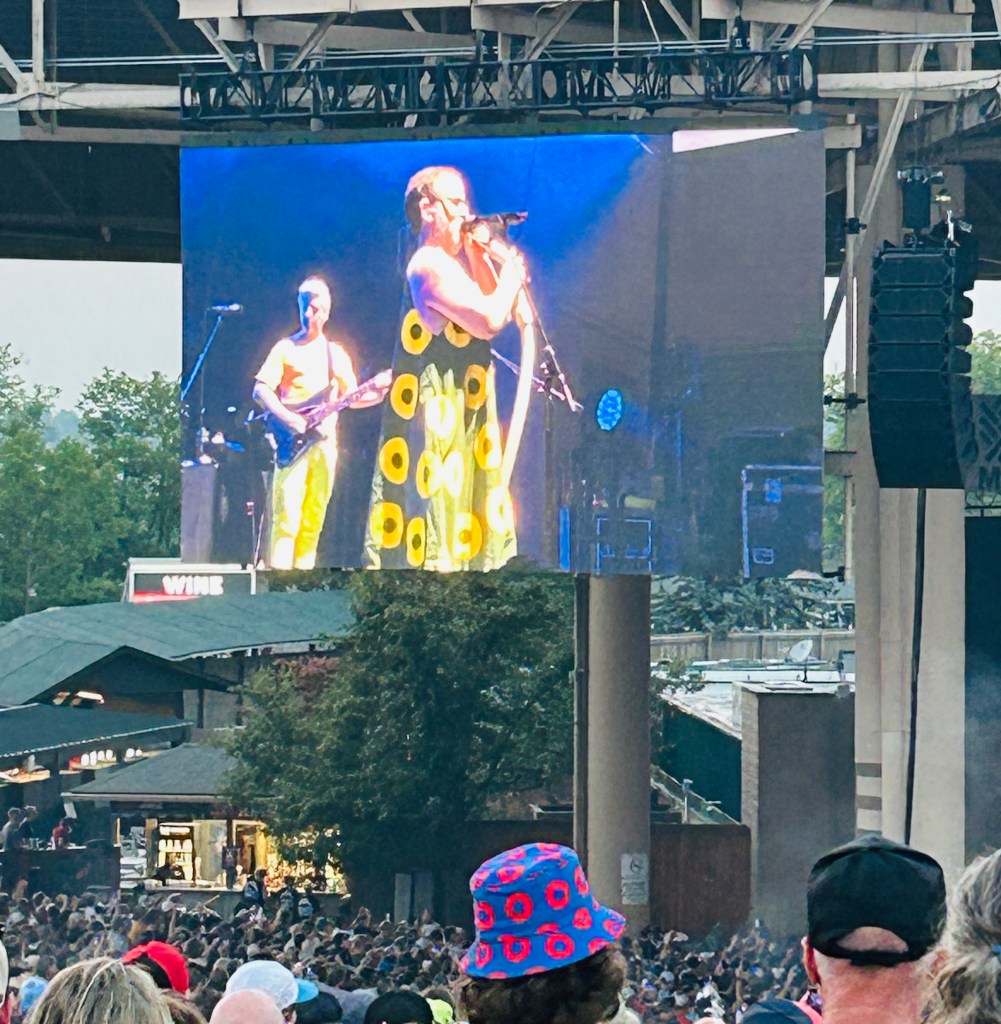

August 3, 2024, Noblesville, Indiana. A quizzical anticipation washes over the restless amphitheater crowd as the short, bespeckled man strides across the stage, dragging a vintage vacuum behind him. The man’s light cotton dress ruffles as the familiar red (or yellow this time?) circles dotting the fabric glow in the oppressively humid evening air.

My eyes remain glued to the giant hanging screen to my left as I watch the band’s namesake, Fishman, carefully place his lips to the end of the vacuum’s hose and … blow.

Jon Fishman makes the Hoover sing. Imagine a cross between a flatulent Kermit the Frog and a beached seal’s whistling lamentation and you might come close to the sounds that emit from the microphone. As the crowd roars in appreciation, I stand on a narrowly folded picnic blanket, stagnant air trapping me, my husband, and our two friends in a sea of drifting marijuana smoke and patchouli-scented, undulating, frequently tie-dye adorned Phish fans.

Suddenly, the darkening sky above me appears to divide between the present and the past. I’m traveling back in time. Waaay back. Thirty-five years in fact.

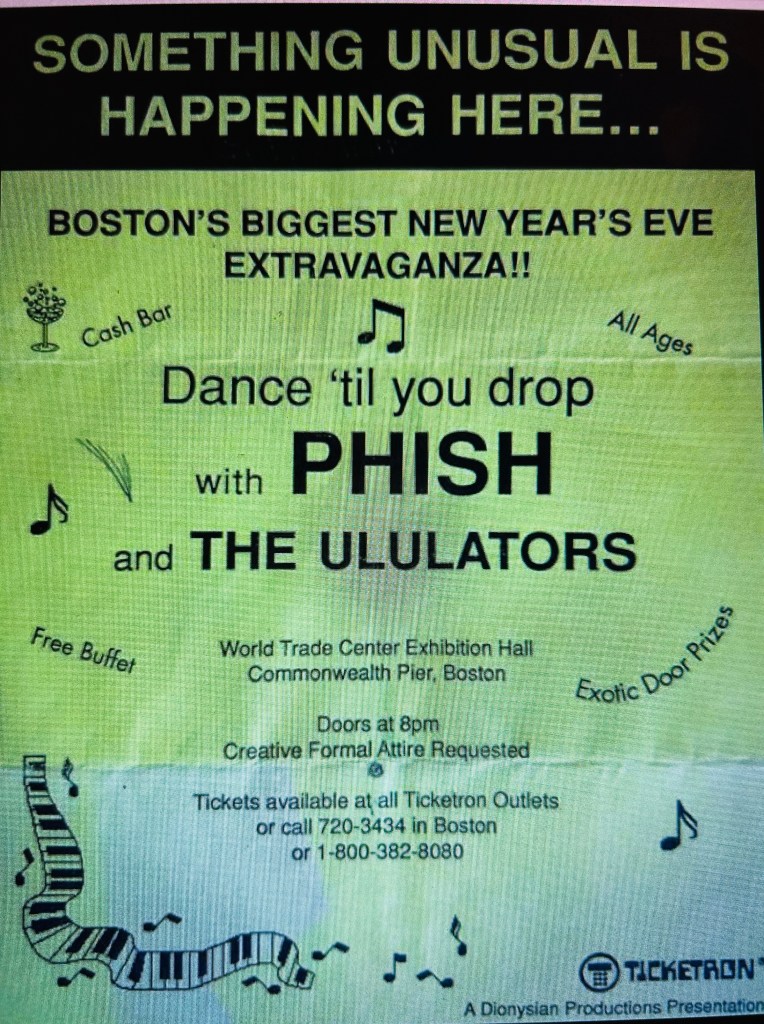

January 31, 1989, Boston, Massachusetts. I am nineteen years old, a recent college dropout sitting on the arm of a floral couch talking to my cousin on the phone, the receiver heavy in my hand. “We’re seeing Phish tonight,” she announces excitedly, “with a P, not an F … they’re hard to describe but I think you’d love them … this is their first New Year’s Eve show ever.” Impulsively (how else does a nineteen-year-old make a decision other than impulsively?) my high-school boyfriend and I decide to see the mysterious, aquatically-monikered band play in Boston that evening.

At that point, the future stadium-fillers only had a handful of fans. Jenny, my older by six months cousin, was first exposed to Phish’s music while attending a very alternative boarding school in Vermont (so alternative that her “roommates” at the institution consisted of her boyfriend and their pet rat—or was it a ferret—and their “dorm” a dilapidated cabin on a wooded Vermont hillside).

That final, frigid night of the 1980s found a group of us stomping along city streets, cold air winding its way under my velvet scarf and straight through my silvery tights as we searched for Boston’s World Trade Center Exhibition Hall, tucked away at the end of a pier. Once inside the wide, dark space we gripped our drinks and watched as the opening band, the popular Ululators, warmed up the festive, eclectic crowd.

Soon it was time for the main attraction to take the stage. A group of four grinning young guys walked out, not much older than us. The two guitar players wore tuxedos and top hats, and the drummer sported nothing but a G-string with tuxedo tails streaming out behind his bare rear.

As soon as the four launched into “I Didn’t Know,” I knew.

While it was clear that these guys were gifted musicians, but something else was also going on, fresh and wholly different. Lyrics were whimsical, clever, and funny. Guitar riffs melodic and transporting, with piano and drums providing both a classic and fresh accompaniment, rousing and soothing the crowd. This was rock music, but it was also a kind of entertainment, a university of the musically absurd.

I’d never seen a band enjoying themselves as much as the crowd facing them. Audience participation was encouraged, as important to the life show’s life as the performers on stage. As the four burned their way through instant classics like “Bathtub Gin,” “Split Open and Melt,” and “Fee” the energy created was reciprocal, as evidenced by the ecstatic grin splashed across the face of the man I later learned was Trey, the enthusiastic, head-bobbing red-haired guy who appeared to be leading the charge.

The notes built and crested and shattered as they rolled around in my head, sometimes all at once. But the highlight, the episode we talked about for days after, was when the red-circle-on-grey-fabric-dress-wearing Fishman (who in my opinion should receive more national credit for normalizing men wearing dresses) rolled a cylindrical vintage vacuum out on stage.

“Maybe he’s going to do a little cleaning,” I thought, “Hoover up the confetti?” Instead, he raised the hose to his willing lips and began to enjoy himself playing the vacuum like an instrument. Our mouths opened in wonderment, the crowd laughingly danced around the room and shook our heads in disbelief. That was it – I’d wager that everyone at that show became a Phish fan for life.

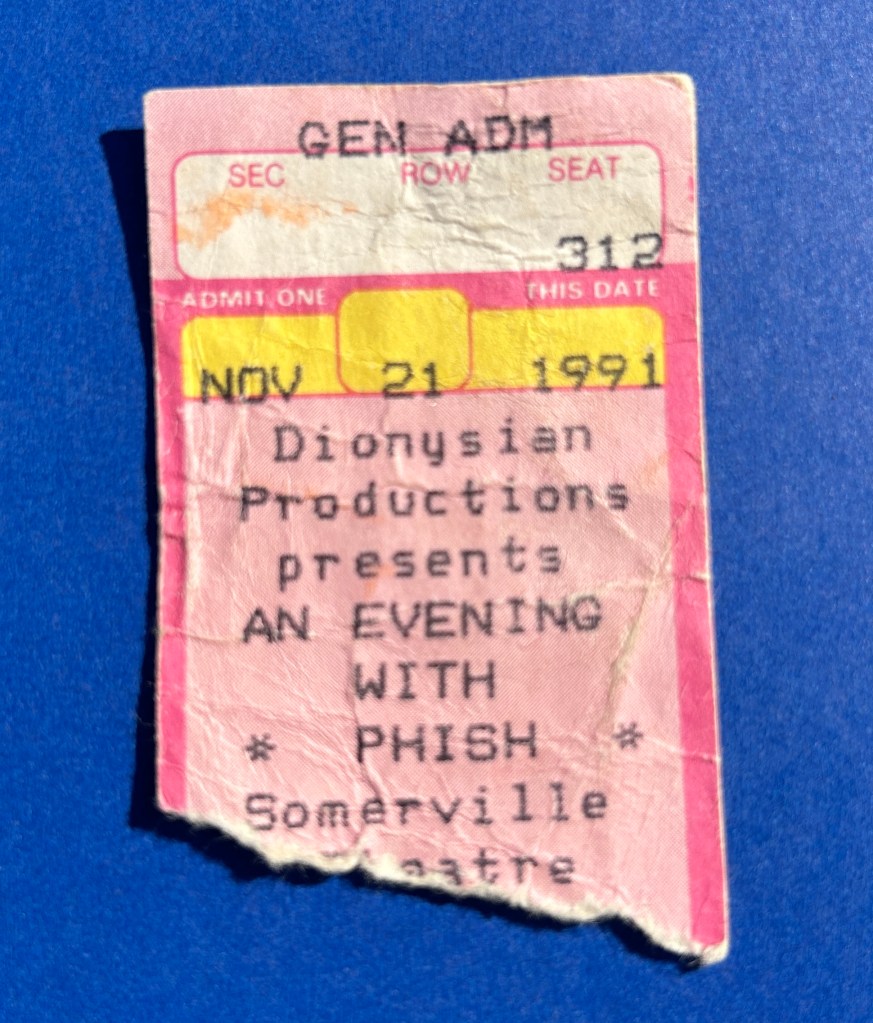

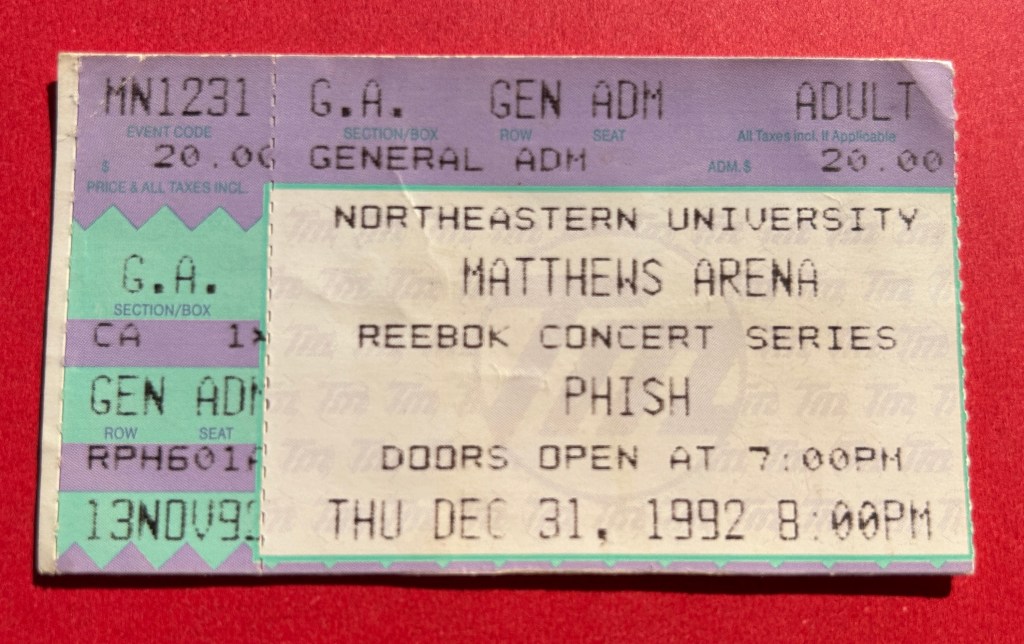

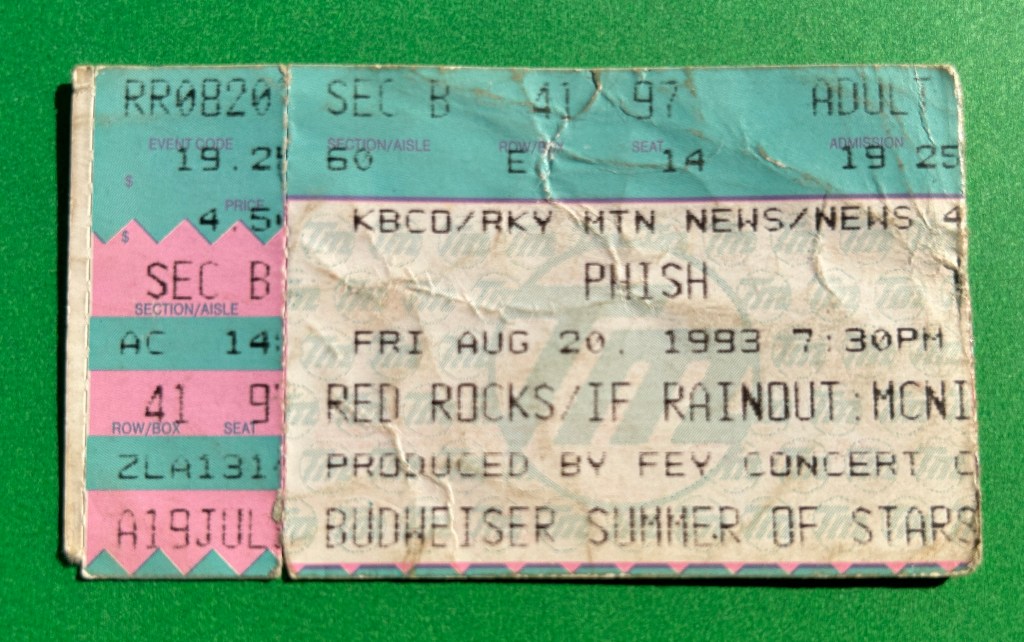

Some of the motley crew that attended the first New Year’s show in 1989 After that first magical night, Phish and their musical movement became a part of my world. Despite an obsession with David Bowie and New Wave music in High School I easily made the shift to devoted Phish fan. I was fortunate to live in Boston throughout the 1990s (which also happened to coincide with my 20s), the same decade the band was rising and growing exponentially in popularity. While Phish launched their brand and collected a gigantic fan base I launched my adulthood, experienced my first broken heart with that first Phish-loving boyfriend, and attempted to discover my place in the world. I never followed the band nationally from venue to venue like a truly dedicated Phishhead, but during those days I saw enough shows in Boston and other Northeast venues to know the words to every song and start a half-inch-thick prized collection of ticket stubs.

Phish ticket stub, 1991 August 3, 1991, Auburn Maine. I had added my name to Phish’s mailing list early on and one day in June 1991 a postcard arrived. It was an invitation to a concert dubbed “Amy’s Farm” because the show was held at the Maine-based farm of Phish’s first fan and friend, Amy. Given that Phish signed with Elektra Records that same year the band was offering thanks in the form of a free show to the fans that had stood by and supported the foursome from their very beginnings in Burlington, Vermont in the early 80s.

This explains how I found myself camping in a dusty field in Northern Maine one hot August day, listening to Phish play under the stars and pines pondering how I got to be so completely free and fortunate. A vague, filmy memory of the band riding out of the thick forest behind the stage, naked, atop horses bounces around my mind, however to this day I’m not certain if this image is a dream, the truth, or a mirage. The sole bummer of the day: we forgot the tent.

Phish ticket stub, 1992 December 31, 1992, Boston, Massachusetts. Another New Year’s show, this one at Northeastern University’s Matthews Arena. Unbelievably, the venue was walkable from the apartment I shared with my best friend in Boston’s South End –no need for tires to make contact with the road. Standouts at the show included the person suspended over the audience in a chicken costume and the mass hysteria signal Trey gave the audience (that I believe was responsible for the “mysterious tremors” mentioned in the Boston Globe the next day). This was also the night I lost track of my group entirely, only to look down from a balcony and immediately spot my friend Nat, his thick bouncing ponytail silhouetted in the immense gyrating crowd like a furry creature signaling his location.

Phish ticket stub, 1993 August 20, 1993, Denver, Colorado. That summer I worked at the Colorado-based camp I’d attended since age six. Phish was playing at Red Rocks and some friends and I managed to get tickets. That evening, I watched the lithe bodies of multiple fans leaping over three benches at a time as the band played “Run Like An Antelope” and the setting sun turned the natural rock walls of the amphitheater a red so brilliant I had to look away.

Watching “the smoke around the mountains curl,” Colorado, 1993 Alas, all was not perfect in Phishland. As much as I enjoyed the concerts, the traditions, and the fan culture I sometimes felt excluded by the masculine energy created by the four men on stage. I got tired of the same jams played by the same dudes with the same expressions and longed to see a woman up there, blending her voice with theirs, or theirs with hers. Where are the female jam bands, I wondered?

The amount of wasted, stumbling, blank-eyed fans who don’t know they are that far gone could be off-putting, even if I was sometimes one of them. Undercurrents of negativity surround certain Phish songs, and I didn’t enjoy the screeching, off-key vocals that sometimes took over. My least favorite song is “Wilson,” which invariably turns into a yell-along for the audience. I do realize, however, that music (especially Phish’s) reflects all aspects of the maze that is the human condition and neither band members, nor fans, are immune to life’s peaks, valleys, and temptations.

July 10, 2003, Shoreline Amphitheater, Mountain View California. In 1998, after ten years in Boston, I moved back to my native Northern California. Soon after, I met my Midwest-raised future husband when our work cubicles were situated next to each other. One of the first things we connected about? Our mutual love for Phish. During the early years of our relationship, right about the time Farmhouse was on permanent rotation in our car’s CD player, we caught a few Phish shows at Shoreline. The most memorable of these was the final show before the band went on a six-year hiatus. Sitting on the lawn at Shoreline, my shoulders sunburned from a day in the California sun, I gazed around at the massive, dancing crowd while the band launched into an encore of “Rift.” It was hard for me to grasp that this wacky little band I had once stood five feet from was now selling out four nights at a 22K-person capacity amphitheater.

Speaking of valleys, Phish’s founder and lead singer, Trey Anastasio struggled with a variety of addictions and was arrested in December 2006. I followed his story closely, perhaps recognizing some of my creative path, as well as addictive behaviors in his, and acknowledging that our idols can be as fallible as ourselves.

In a January 25, 2019 interview with GQ magazine about his embrace of sobriety Anastasio remarked “You know, I look to my heroes to be reminded that really good, really smart, really talented people can fall into this trap pretty easily, far down the road, if they’re not careful. The important thing is to know that there is a way out. And the life at the other end of that is a beautiful life. Everything bad turns into an incredible gift. If people can find the way out.”

Mistakenly, I thought a sober, creative life would be about as exciting as a bleached sample in a jar, but I assure you, just as Trey has, that it is even more beautiful and exciting than anything that has come before.

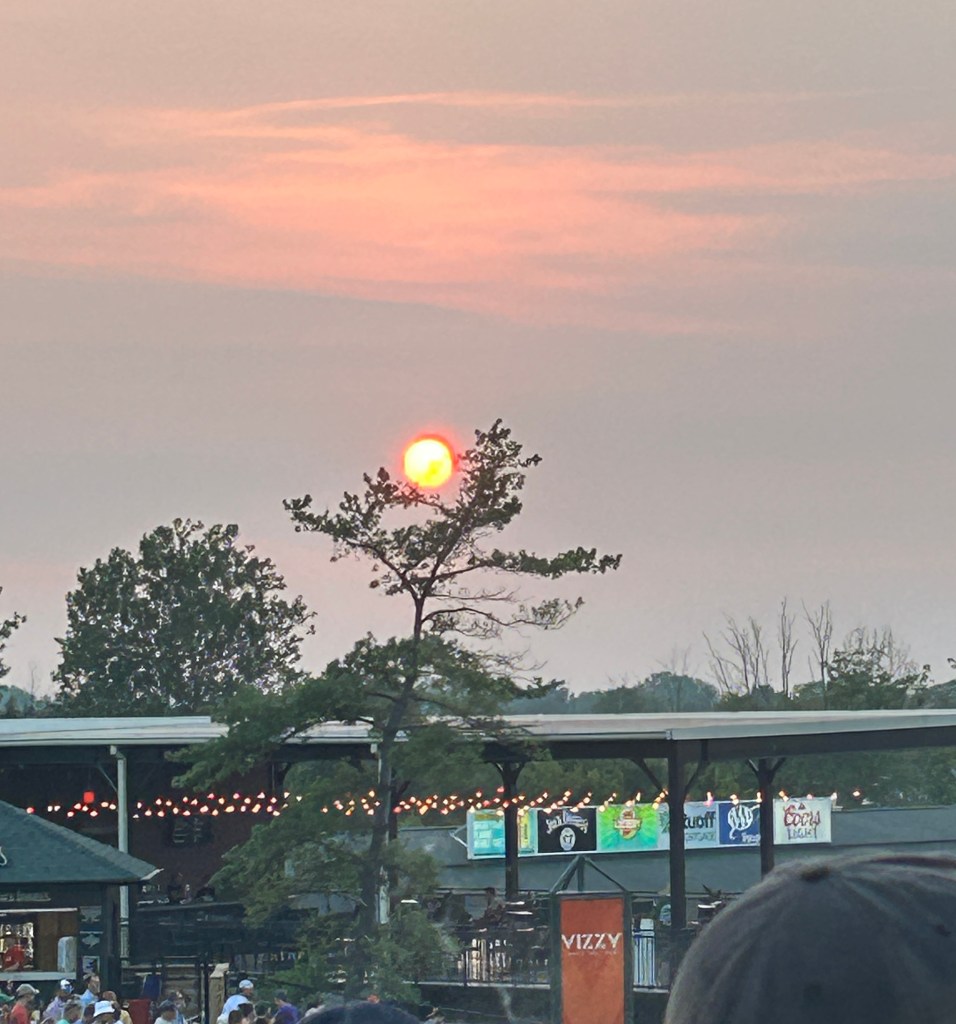

Caught between the past and the future, Arizona, 1995 August 3, 2024, Noblesville, Indiana. Back on the lawn at Deer Creek (as Hoosiers will forever insist on calling it), the glowing orb of a setting sun is held by the branches of a lone tree. I am content, the kids are safe at home and my grooving, grinning husband of eighteen years dances alongside. I have been held by Phish’s music for so long that it has become a part of me, the branches of my life growing around the always-evolving but forever-burning core.

Sunset at Deer Creek, August, 2024 And miraculously, thirty-five years after first hearing the tortured sounds emitting from Fishman’s vacuum hose, I am listening to them once more.

Look back but don’t stay too long. Note: Special thanks to Phish.net which provided many clarifying details to my sometimes (okay, often) hazy show recollections.

-

Remembering Cypress

This is only the second turtle visitor we have found

on our property in 9 years.Every year something special seems to happen on this day — this morning a (rare) turtle visited my husband in the garden. In the afternoon, I took a hike with an old friend where the breeze caressed my cheek, the sunlight dappled the trail ahead and the trees seemed to reach out their limbs in comfort and praise.

Rainbows have stretched over us on this day, unexpected flowers have bloomed, and one year the first dragonfly ever glimpsed in our garden made a brief, brilliant appearance.

Tonight, our family will mark the day by gathering to light a candle, as we always do on May 20th.

Fourteen years ago, this day was not a celebration. My oldest son Cypress was born at full term, but he was not alive. I’m always full of conflict when the anniversary comes around. Part contemplative, other parts sad, proud, happy, and tired. Also, oddly energized.

Fourteen years ago, instead of cradling a crying, radiant newborn, we sat in a silent, cold hospital room, heavy with grief and pain. Birth most often brings gifts of joy, relevance, and new life. But Cypress did not get to live out his earthly life, and that fact can feel punishing and cruel. The truth is, on the day of his birth I was swimming in so much physical, emotional and spiritual pain that I couldn’t imagine ever feeling joy again.

As always, the forest comforts, provides solace, and accepts me as I am. However, to my amazement, not only have I felt joy again, his birth and the nine months I cradled him close to my heart have also brought great gifts. Slowly, the value of those presents have unfurled over the years. My understanding of the meaning and truth of life has deepened and expanded. I’ve become more compassionate, patient, realistic and loving since becoming Cypress’ mother.

In the early days of my loss I hardly wanted to be around babies, pregnant people or children. Protecting myself and my heart felt necessary. Nowadays my two living kids and my work as a preschool teacher ensure that I have daily contact with children, their lives, their challenges, their growth, their joy.

Growth and rebirth never stop, for plants and humans both. It is clear to me that we have as much, if not more, to learn from children as they do from us — if we are willing.

No longer do I neglect my talents, numb my mind/pain, ignore what requires attention. I understand our time here on this beautiful blue-green ship must not be wasted, pushed away, or taken for granted. Besides that first awful year after his loss, bitterness, self-condemnation, hate, and depression have not won. I’m determined that they never will.

Despite material appearances, we are still connected to our oldest child, he will forever be a part of our family. That’s why special things happen on this day (and other days). Cypress is close, he would like to reach and teach us if we open our hearts and recognize his presence. In turn, I can offer him the mothering he still waits on and needs from me.

The sun ray captured yesterday in the garden made me think

there might have been a third presence (in addition to the cat).He is wise, thoughtful and funny, my oldest son.

Strengthening connections to those we love who have passed on brings rejuvenation and healing to our minds and hearts.

And there are some days we need it more than others.

-

Adventures in Church Hopping

When I was growing up in California in the 1970s and 80s, church was quiet.

At 9:55 am on Sundays, I parted ways from my parents and headed to the Christian Science Sunday School where students of all ages gathered to sing a hymn. Immediately afterward, our teacher gathered us up like chicks, pulled two heavy accordion doors shut, and sealed our class of five or so into a cramped room. There we sat around a pine table in our hard cane-backed chairs, earnestly discussing the meaning of God and Love.

Other times, when I joined my mom at Wednesday night testimony meetings at the same church, we sat thigh-to-thigh together in the half-full edifice, listening to people (most over the age of forty) as they stood and shared their accounts of spiritual healing. An organist accompanied the congregation’s soft, hushed singing voices, and my mother often shushed me as I fidgeted in the pew and shifted my restless legs.

Back then, church meant learning about God and healing, and being with my family. Sometimes, when my grandparents or extended relatives visited, we took up an entire pew (I was allowed to skip Sunday School on those days), and then piled into separate cars to drive down Hwy. 12 to the Chuck Wagon cafeteria where I had permission to eat as many marsh-mellow dotted Jello’s as I could fit on my tray.

The Christian Science branch church in Bloomington, Indiana Fast forward to today, where I live in the small (but growing) city of Bloomington, Indiana in the Midwest of the United States. And for the moment, let’s put aside the decades of spiritual wandering, questioning, doubting, seeking, and finding that have passed since my early church experiences. Those details are for another post (or book – wink wink).

Over the past year or so my friend Hether (who grew up in the same church I did) and I have been practicing what we call “church hopping.” About once a month (not every Sunday thanks to baseball, soccer, and…life) we pay a visit to a different congregation. Sometimes we have a connection to the church, other times we don’t know a soul.

The dome at the Monastery Immaculate Conception Catholic Church, Ferdinand, Indiana We’ve only scratched the surface of the large number of churches that dot our town, let alone state (visiting fewer than ten different faiths so far), but the exercise has been thought-provoking and eye-opening. Among other things, what’s become clear to me is the vast range of religious and spiritual experiences we humans require and yearn for — so many people need regular gathering/support/community, inspiration, and yes, even entertainment.

Individual pastors have a whole lot to do with setting the tone for a church, I’ve noticed. In my church of origin, Christian Science, (not to be confused with Scientology), the “pastor” is comprised of two elected “Readers” who recite aloud to the congregation passages focused on a weekly theme. The readings come from two books: the King James version of the Bible and Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy. While services are often thought-provoking and inspiring, you can pretty much anticipate what you’re going to get each time. There are very few material surprises in the Christian Science church.

The soaring sanctuary in the Unitarian Universalist Church

of Bloomington, IndianaBut now, after experiencing a variety of different pastors preaching to their congregations, I’ve seen that each pastor brings their interpretation of scripture, God, or the world of spirit to the podium. In many cases, a pastor’s outlook becomes the lens through which their congregation views the world.

And the music! To go from generally solemn, sedate organ or piano music to an entire band rocking, soaring, and singing ear-splittingly loud “worship” music accompanied by a light show and multiple massive screens has been, to say the least, disconcerting. The first time Hether and I attended one of these “contemporary Christian” churches I was, honestly, sitting in wide-eyed shock for most of the service.

Something else has occurred to me through these visits: It’s possible that I feel more comfortable, inspired, and accepted meditating in a temple, shrine, or ashram with the scent of incense threading through the air than I do inside a church building. Or, maybe instead of getting caught in comparisons I can acknowledge that each location of inspiration offers its own unique value.

Stupa at the Tibetan Mongolian Buddhist Cultural Center

(founded by the Dalai Lama’s brother) in Bloomington, IndianaThis Sunday, Hether wasn’t available, but my ten-year-old daughter was. “Let’s visit the big church, Mom” she suggested. The “big church” is the one closest to our house, a sprawling mega-church with six entrances that holds three services each Sunday and hires a cop to direct traffic in and out of the parking lot. I think my daughter was just as curious as I was about what goes on inside the building whose grounds we have walked and played on for years.

After parking in one of at least twenty specially designated “First Time Visitor” spaces, we were enthusiastically greeted and directed to a computer to enter our contact information, then handed a welcome bag (containing pen/notepad/church logo plastic cup/stickers) and directed to the children’s wing. My daughter, however, did not want to join the youth classes and instead opted to sit with me in the main sanctuary for the service.

While helping ourselves to a quick coffee and hot cocoa from the well-stocked café space we spotted a (lovely) familiar face, our friend and former neighbor who invited us to sit with her and her husband during the service. “I can’t wait to see his face when he sees you, he’s going to be so surprised and happy,” she said about her husband. My daughter, who adores this couple and once spent Christmas Eve with them due to an emergency in our family, happily sat down in the pew next to them and basked in their love and attention. This is the first time she’s sat in church with her elders I thought to myself.

Sherwood Oaks Christian Church, Bloomington, Indiana

You know a church is big when it has a “Worship Center North”“Wow, this isn’t what I expected, it’s not very church-like,” my daughter whispered to me as the lights dimmed, the band with four vocalists stepped out on stage and the loud music began filling our ears. Given her (admittedly limited) church experiences in the ten years she has been on the planet I didn’t blame her for being taken aback.

We sat together through the service, my arm tight around her shoulders, absorbing the resounding music and listening to the sermon. The pastor’s message, centering on divine reminders to rest, and step away or remove obstacles and stressors from our lives rather than pile on more, resonated with me. In the end, I think my daughter was mostly impressed with seeing our friends, and the chance to sip on hot cocoa before noon.

An important message outside the First United Church (combined Baptist and United Church of Christ)

Bloomington, IndianaLater that same day, after yet another church visit (this time for a beautiful and inspired blended poetry and song performance by the poet Ross Gay and our local Voces Nova choir), Hether and I sat outside in the soft spring evening air. Our discussion returned to our spiritual paths (as it so often does).

“I’m not totally sure what I’m looking for as far as church,” I told her plaintively. “I mean if I could design my own what would it look like?”

It’s actually an interesting exercise, designing one’s one church. If you’d really like to know, my ideal church would be one that accepts all colors and creeds, features time for silent prayer, an inspirational healing message, some guided meditation, rotating musicians, and a little stretching/yoga/Pilates during the service. All in an old-growth forest cathedral.

If anyone knows a church like that, let me know.

In the meantime, we’ll keep searching, listening, and hopping.

-

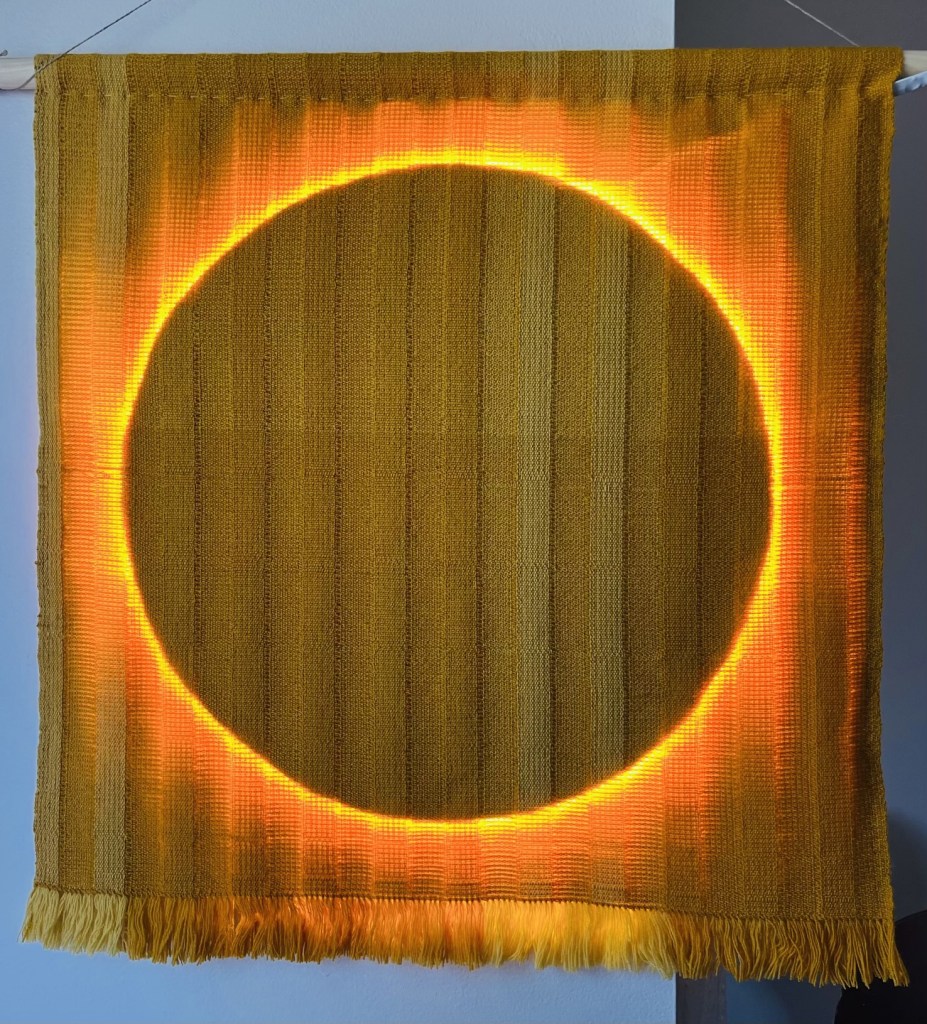

27 Hours and 42 Minutes in the Life of a Total Solar Eclipse

“She Swallowed the Sun” by Chelsea Holden Gurney,

currently on exhibition at I Fell Bloomington

in Bloomington, Indiana, USAApril 7, 2024

1:49 PM: With a start, I realize tomorrow is THE DAY and that we live in the ZONE OF TOTALITY. What’s going to happen, am I ready? I scramble around, pulling out hoarded eclipse paraphernalia. Counting 3 eclipse guides and 13 pairs of glasses gathered over the past year. Will we have enough?

2:42 PM: My daughter and I drive to the “There Goes the Sun” celebration at our local Bloomington, Indiana Switchyard city park and amphitheater. Traffic is light and I consider whether we have worried unnecessarily about eclipse crowds – some reports have suggested that 300 thousand people may descend on our town. A pop-up vendor is selling tie-dyes and eclipse t-shirts on the street corner. Why the tie-dyes?

Are there vendors that follow in the path of eclipses? 3:04 PM: We enjoy the first strains of local son Hoagy Carmichael’s “Stardust” played by the talented Bloomington, Indiana Symphony Orchestra, and accompanied by the Voices Novae choir. Catching the contagious feeling of camaraderie and expectation floating around the crowd, we sit on blankets, snack on dried fruit and watch children dance.

Listening to music at Switchyard Park. 3:50 PM: Audience sing-along to “Total Eclipse of the Heart” by Bonnie Tyler. The classic song was released in 1983 so most people born in the 1970’s or before appear to know the words by heart (personally, I am transported back to the fraught days of middle school dances). My daughter and her friends read the lyrics on a cell phone and the entire crowd sways in unison singing;

“Your love is like a shadow on me all of the time (All of the time)

I don’t know what to do and I’m always in the dark…forever’s gonna start tonight.”

Cross-generational pop music. 6:41 PM: Odd weather. Rain and sunshine in the front yard. Rain and dark clouds in the backyard. Reports of rainbows in the vicinity.

Sunshine through the raindrops. 8:00 PM: We cancel plans to attend a friend’s neighborhood eclipse glow party at a park shelter due to approaching thunderstorms and return glow stick supplies to the garage.

April 8, 2024

9:19 AM: We wake up with a feeling of anticipation, much like a birthday. My husband (infamous for retaining birthdays) informs me that today is Gary Carter (his all-time favorite baseball player)’s birthday. April 8 is also the birthday of a friend’s son, along with the birthday of the pastor of the church that houses the preschool where I work. Good signs all around.

Happy Birthday to Gary Carter. 10:21 AM: Pack eclipse picnic lunch: Peanut butter & jelly sandwiches for the kids and their friends who will be joining us, leftover Chinese noodles for the grown-ups, chips and salsa, orange slices, Newman’s O’s, sparkling water, and juice.

11:34 AM: Pack wagon for the journey to the eclipse viewing party.

12:10 PM: Depart for a ten-minute walk to a friend’s back garden patio, adjacent to a wide-open green space behind a mega-church (three services each Sunday). Here is where we plan to view the eclipse, on a gently sloping green lawn practically designed for the occasion. Pulling our packed wagon behind us we see people streaming into the church entrances and stopping at welcome tables. Is the church charging people to use their lawns, we wonder, or are they just giving out water?

We never used the folding chairs once. 1: 22 PM: Our group of ten is assembling – my husband and our host (a close friend) our two children and their three friends. Two more friends arrive on their bikes—one is a scientist (a biologist). She knows stuff about nature! We eat lunch and excitedly chat with neighbors. The three 11-year-old boys run off to play basketball, promising to return in a half hour. The light already appears diffused, almost cinematic.

Total Solar Eclipse: Garden party style.

Photo credit: Hether Bearinger1:49 PM EST Partial Eclipse Begins. Anticipation is rising, crackling in the shiny air surrounding us. Everyone chooses glasses, noticing that some tear or bend easily, and others are uncomfortable and too large, especially for smaller heads. The type with one solid strip that looks like a viewfinder is surprisingly effective. We have more than enough glasses. Vaporous filmy clouds drift in front of the dimming sun, best viewed through a pink veil of weeping cherry blossoms.

2:22 PM: “USE YOUR GLASSES WHEN YOU LOOK AT THE SUN” we remind the kids, and occasionally the adults. The sun looks like a blob of egg whites with a small bite taken out of the lower right-hand corner. Where are the boys?

Egg white sun with bite.

Photo Credit: Hether Bearinger2:44 PM: Someone gets out a strainer and we try various surfaces, finally landing on the adjoining neighbor’s smooth patio flagstones. Numerous tiny crescent moons appear on the sandstone below. The kind and friendly neighbor, who recently turned 80 and is recovering from major back surgery, gasps in amazement.

When a common kitchen strainer takes on a heroic role. 2:51 PM: We have left the patio and are now gathered on the wide-open lawn area, taking pictures, gazing at our changing surroundings, and talking in small groups. We are glued to the sun, our faces tilted up expectantly. The temperature has dropped, and the wind has picked up. It appears to be twilight and the birds are beginning to sing like they do at dusk. Energy seems to swirl around us, as palpable as electricity. Suddenly the boys run up, sweaty from basketball. “Did we miss it?” they ask breathlessly.

The reason our necks are sore. 3:04 PM: Totality Begins. We have watched the bite in the sun grow bigger and bigger and suddenly, like a cap fitting neatly on top of a bottle, the sun is gone. We tear our glasses off our faces and gaze directly at the sun. Nighttime has descended and it is becoming as dark as when you stumble to the bathroom at 3 AM. The horizon glows in every direction as if a sunset is encircling the earth.

What totality looked like to the naked eye, except darker.

Notice Venus at lower right.3:06 PM: Midpoint of Maximum Totality. Awe ripples across the lawn, embracing all of us with its fierce insistence. Gasps, screeches, and exclamations reverberate in all directions. Things that take me by surprise: complete darkness, tears streaming down my cheeks, the feeling of vulnerability in the face of a vast cosmos. All this in tandem with a sense of swelling love for my fellow exquisite humans. Below the eclipse, to the lower right Venus catches my eye, winking in the black dome of sky. Reaching out, I kiss my children and my husband and hug my friends, who are also crying. In my excitement, I attempt to take a video, which later turns out to be a shaky scene of dim grass at my feet.

Glorious “diamond ring” totality, taken in Bloomington.

© Jason Brown http://www.jbcreative.photo3:08 PM: Totality Ends. Marveling, we gasp as the warmth of the first uncovered sun rays begins to touch our arms and faces. The immense power of the sun has never been clearer to me. Without it, life as we know it is no more. Without the sun, without light, we exist in darkness. Beautiful darkness, but darkness, nonetheless. A knot of people mumbles in the distance, stooped over searching for dandelions that have closed in the darkness. “It’s like we’re in a movie,” remarks my son.

4:22 PM: Partial Eclipse Ends. “We can use these glasses even when there’s no eclipse,” the kids remind us. Our necks are sore from stretching skyward. We are wrung out from the afternoon’s experience. Everything around us feels slightly different, transformed in some way. Humans, plants, and animals included (later my daughter coaxes a raccoon out of a tree in our neighbor’s yard — the animals were equally as discombobulated).

Absorbing the wonder of totality. 4:30 PM: Walking back to the patio, I try to articulate to myself the message embedded in the grand cosmic display we have just witnessed. This total eclipse occured in the middle of my life, but my children are still forming! I know they will remember this forever. How desperately this planet needed this experience at this moment in time. It is as if the universe was saying “Stick together humans, love each other in the face of the vastness of space. There are many forces you can’t control, but your survival IS within your reach. Love yourselves, love the past and the present and the NOW. Stand in awe of the universe.”

At least that’s what I got.

-

Taking Time to Talk, and Trust

When someone deeply listens to you

It is like holding out a dented cup

You’ve had since childhood

And watching it fill up with

Cold, fresh water.

-John Fox, Finding What You Didn’t Lose

I’ve had some unusually deep conversations lately, ones that touched on topics we humans are pretty adept at keeping to ourselves. Abuse, pain, addiction, failure. So often we bundle and wrap our sorrows, issues, and dreams like hoarded and expensive presents, presented infrequently and with trepidation.

A friend once described to me what her Chinese grandfather would do when she banged or bumped herself to avoid bruising: he would press his fingers into the afflicted area and knead it with great force. She loathed this and learned to run in the other direction and hide in a closet when she hurt herself around him.

My friend’s childhood solution reminds me of the impulse so many of us have – don’t delve too deeply into the pain because you might expose yourself, and it’s going to hurt. Don’t reach out or share what happened with anyone. Instead, run away quickly and shut the door quietly.

Why do we avoid talking about difficult things, when sharing, supporting, and loving each other is perhaps the most meaningful thing we can do as humans? I see it as a two-fold issue: the first is trust and the second is time.

Establishing trust with another person is fraught with minefields. From our very beginnings, the muscle of trust is exercised. We require food and shelter, love, and learning. Sometimes, those who are tasked with our well-being fall short and we can live our lives carrying that knowledge like the heavy baggage it is. If I couldn’t trust then, why should I trust now? The tender, fragile petals that make up our seemingly impenetrable armor are easily trampled on. And even if you are fortunate enough to avoid childhood trauma, at some point in our collective lives, betrayal is a given, whether the source is family, friends, romantic partners, employers, society, or otherwise.

Heck, I’m currently writing an entire book on how I worked through feeling betrayed by God.

And then there’s the issue of time. Carving out the opportunity and space to share deeply can feel like the least important thing on one’s list. The conversations I referred to earlier happened in the following places: a coffee shop, a friend’s living room, and an art supply closet. Two planned, one not. All three offered me deep solace, information, and inspiration I didn’t consciously know I needed.

Our lives, packed with work, survival, and to-do lists, do not often allow room for the unfolding of leisurely, unstructured, open conversation. But when the stars align, when people reach across the table and hold a friend’s hand, or share their deepest thoughts, fears, and hopes a rare, healing alchemy bubbles up. We feel connection, relief, understanding. The tattered fabric of our hearts stitches back together. Walking forward with a lighter load, even a few solutions, is possible because we have been heard and understood, and we know someone else has laid down some baggage too.

Back to my friend’s grandfather’s folk remedy: if the whole point of massaging the hurt area was to avoid bruising, that must be what we do for each other when we connect, when we listen without judgement. We help each other heal the deep bruising.

That is, as long as we make time for it and don’t hide.

-

Nepal Part One: From College to Kathmandu

It’s hard to imagine a clash of cultures more extreme.

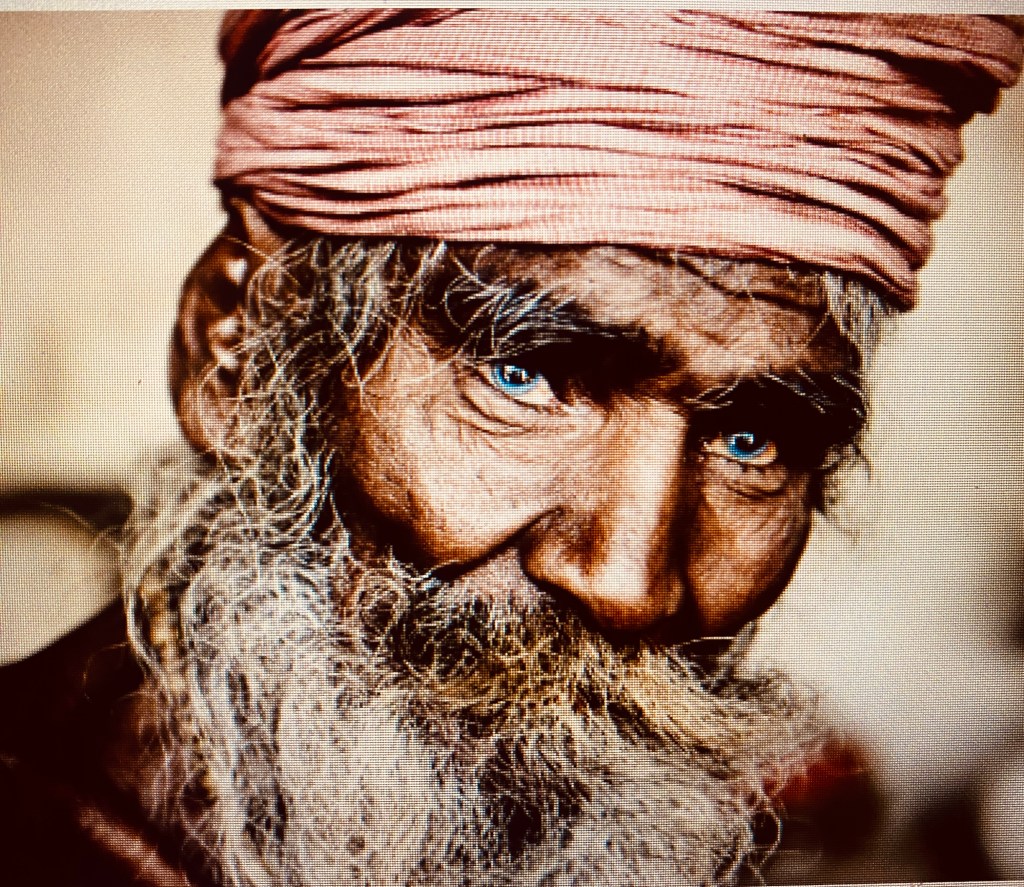

Standing in awe of a stupa, and the country of Nepal. In the final year of the 1980’s my eighteenth birthday is spent illicitly drinking beer at a Christian boarding school in St. Louis, Missouri in the flat middle of the United States.

Twelve months later I celebrate my nineteenth in complete silence at a Tibetan Buddhist monastery nestled in the steep foothills of the Himalayan Mountains in Kathmandu, Nepal.

The Royal Nepal Airlines flight touches down on the Kathmandu tarmac with a sudden, jarring bounce. My head is still spinning from the awe-inducing Himalayan landscape I’ve just seen out the window. Standing unsteadily, I move so that the mostly Indian, Pakistani, and Nepali passengers can disembark around me. I’ve been to the Sierra Nevadas, climbed a few 13ers in the Rockies, and explored quaint villages in the Swiss Alps. But now I understand that those ranges are mere foothills compared to the jagged snowy peaks streaked with dark grey that stretched for hours beneath and beyond the airplane. These mountains appear to have no end—they ripple out in every direction, nearly swallowing up the sky itself.

My first sip of the Himalayan Mountain range brew tells me all I need to know—over here, on the other side of the earth, nothing is the same.

Six months earlier I started my freshman year of college, mostly because I had no idea what else to do. After a single semester, it was clear that I wasn’t going to find the answers or direction I was looking for within the walls of an institution, so I dropped out. After twelve consecutive years of school and an ill-advised college enrollment, I found myself limply dragging my mediocre grades and minor accomplishments behind me.

Exactly when had I lost the soaring confidence I’d had when I was younger? Despite my privileged, white, upper-middle-class first-world life I was a confused, timid, mildly depressed version of myself. Entirely unclear about what I was good at in life, what I believed, and what lay ahead of me, I was sick of STUDYING the world. Instead, I wanted to EXPERIENCE it. Although everyone kept asking me what I wanted to major in (I mistakenly thought the answer to that question would determine my entire future), I could barely decide on which of my circle of friends were trustworthy and what music I actually enjoyed listening to.

My mostly sympathetic parents offered a solution: they would front the funds they would have spent on my education that spring semester provided I did some sort of program, ideally one that would offer me college credits. When I learned about a months-long “Experiential Learning” program in Nepal I knew it was for me (I also acknowledge that I was the beneficiary of unusual privilege in that I was able to both attend college and visit Asia in the first place).

A couple of months later I find myself on that Royal Nepal Airlines flight, embarking on the adventure of a lifetime.

I am eighteen years old.

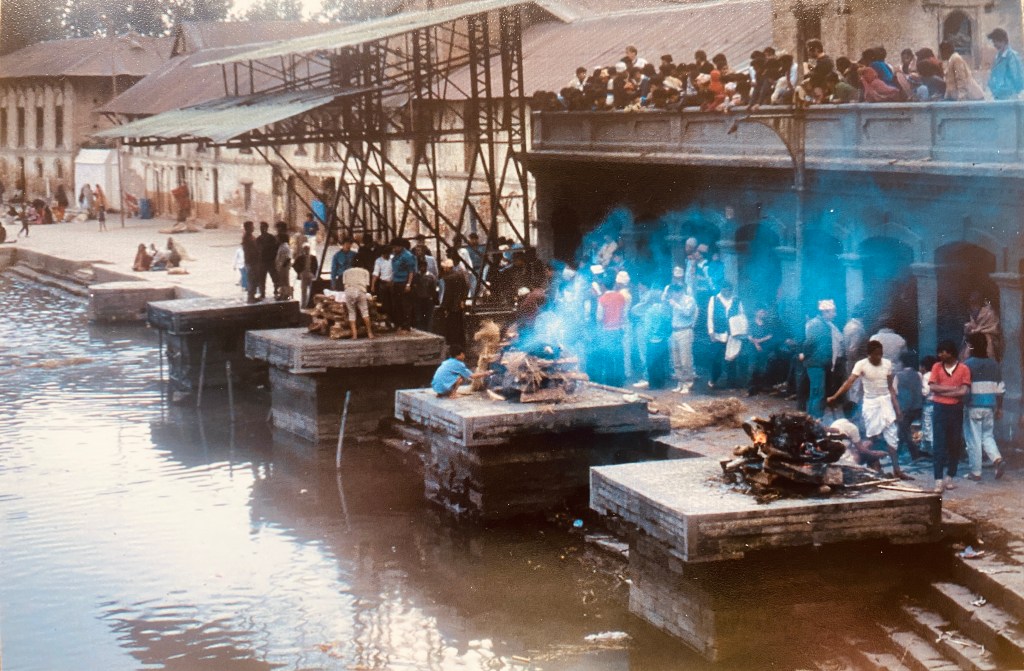

On paper, the details of our Spring 1990 Nepal program are straightforward: the group of approximately fifteen of us will live together in Kathmandu while studying the Nepali culture and language. The itinerary includes a month-long homestay with a Nepalese family, an optional ten-day retreat at a Tibetan Monastery, volunteer time with a local organization, a forty-day trek to Mount Everest Base camp at 17,598 feet in the Himalayas, and a final foray into the rhinoceros-infested jungle in the flatlands of Nepal.

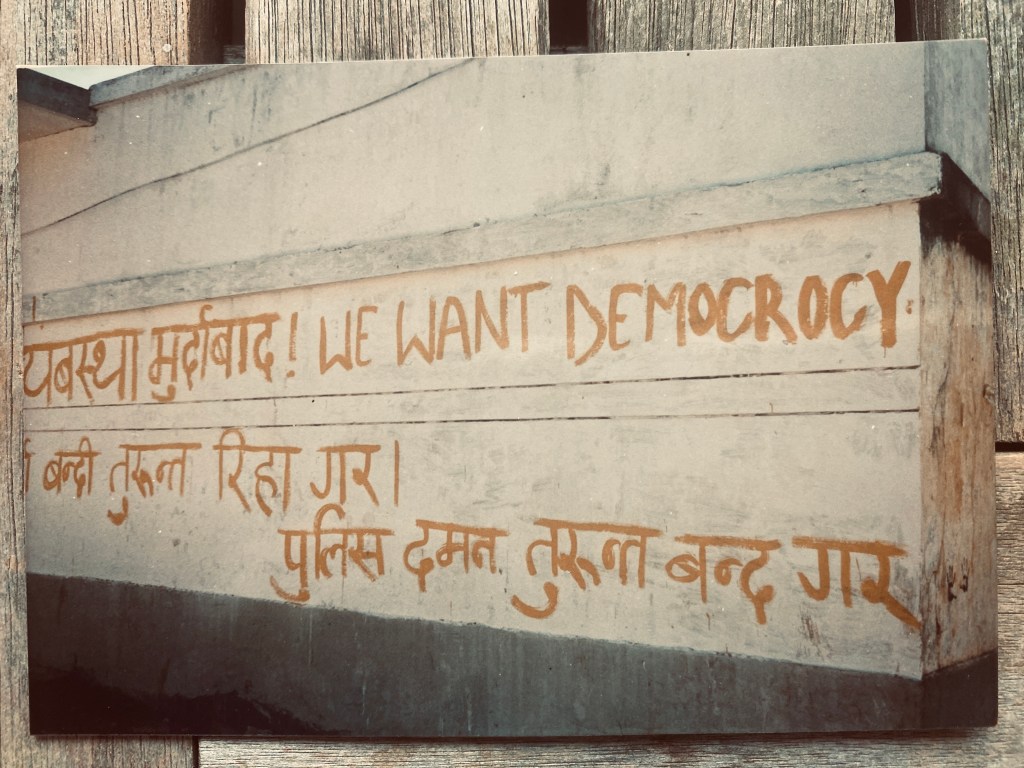

As if that list isn’t enough, something else is going on in Nepal that wasn’t exactly factored into the itinerary: a political revolution. A primarily student-led movement is rising in resistance to the royal monarchy that has exclusively ruled Nepal for centuries. The protesters want a constitutional monarchy (essentially a system of government that limits a King or Queen’s absolute power and includes…wait for it…a constitution). The number of Nepali demonstrators is growing by the day, and protestors are willing to stand up, be shot at, and fight for their independence. Parts of Kathmandu are in turmoil and there are rumblings that our program may be cut short.

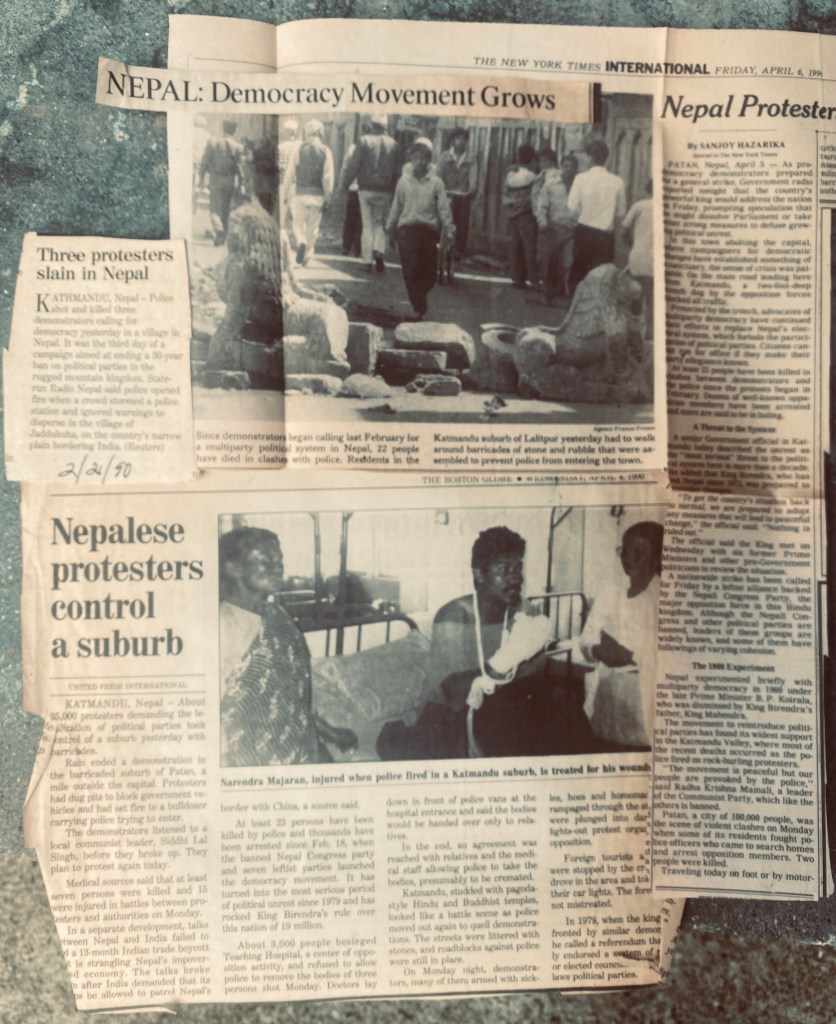

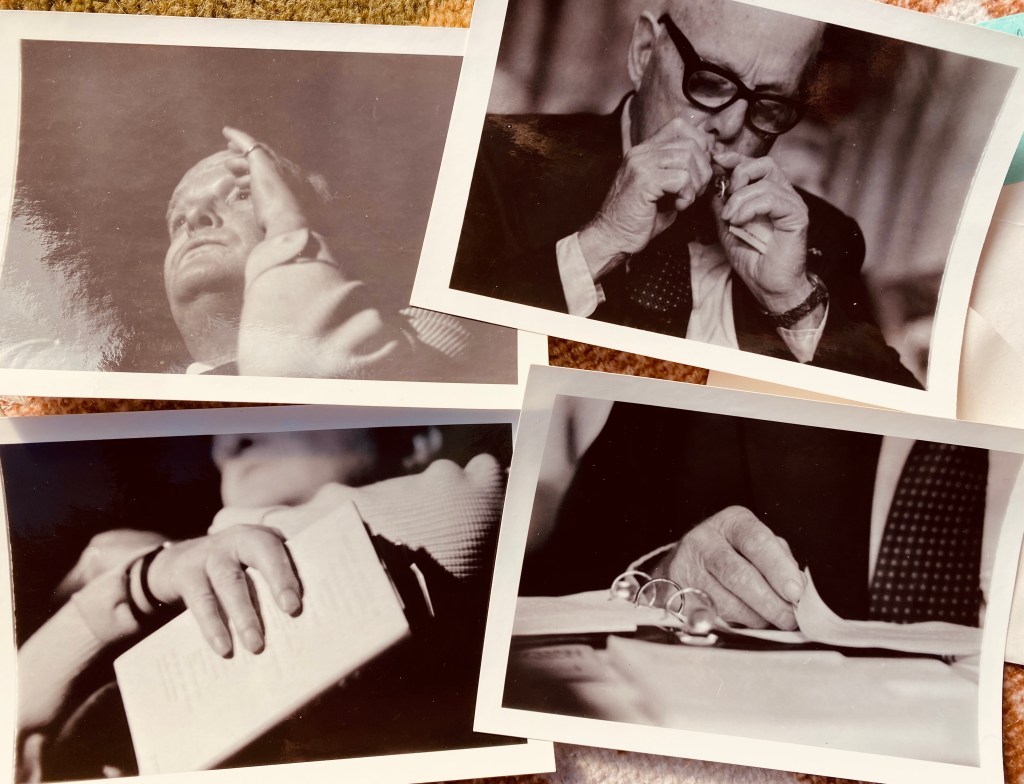

When I return from Nepal my father hands me six months of

press clippings he has carefully saved.Our bunch of students is a hodgepodge of mostly East Coast characters from the US ranging in age from eighteen to thirty-one. Many of the group are students at Ivy League universities and I quickly learn a valuable life lesson: admission into Harvard or Yale does not necessarily mean one has more street smarts, empathy, or knowledge about day-to-day survival (on the road or otherwise) than anyone NOT attending a top-tier university (or than those not attending college at all).

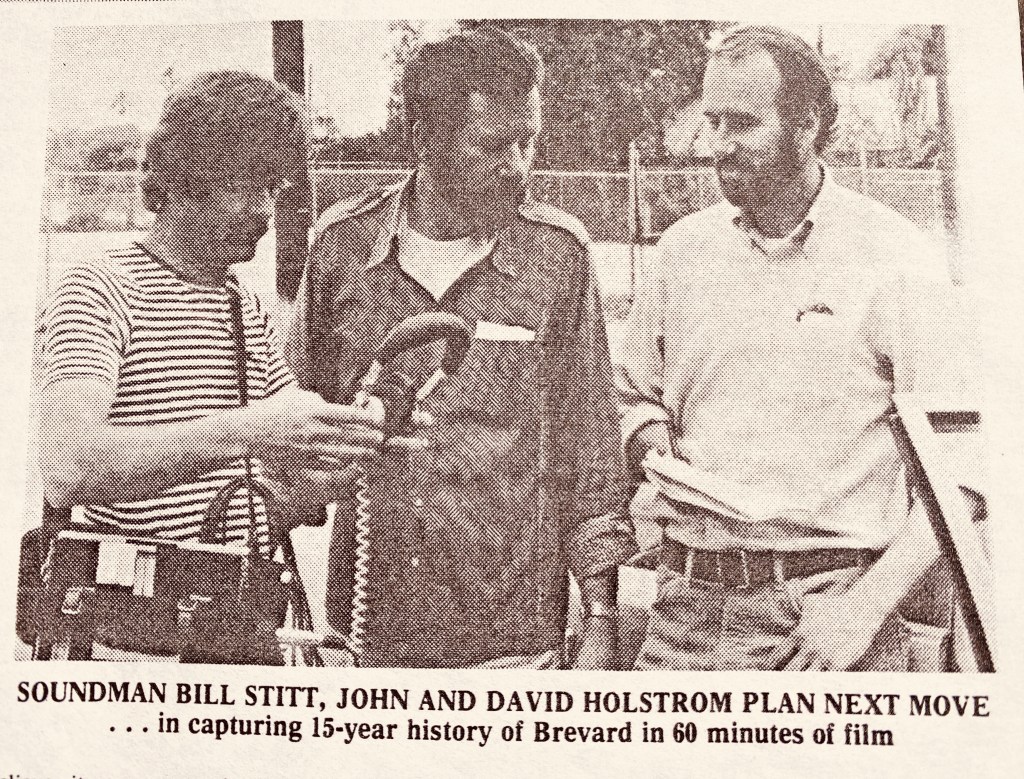

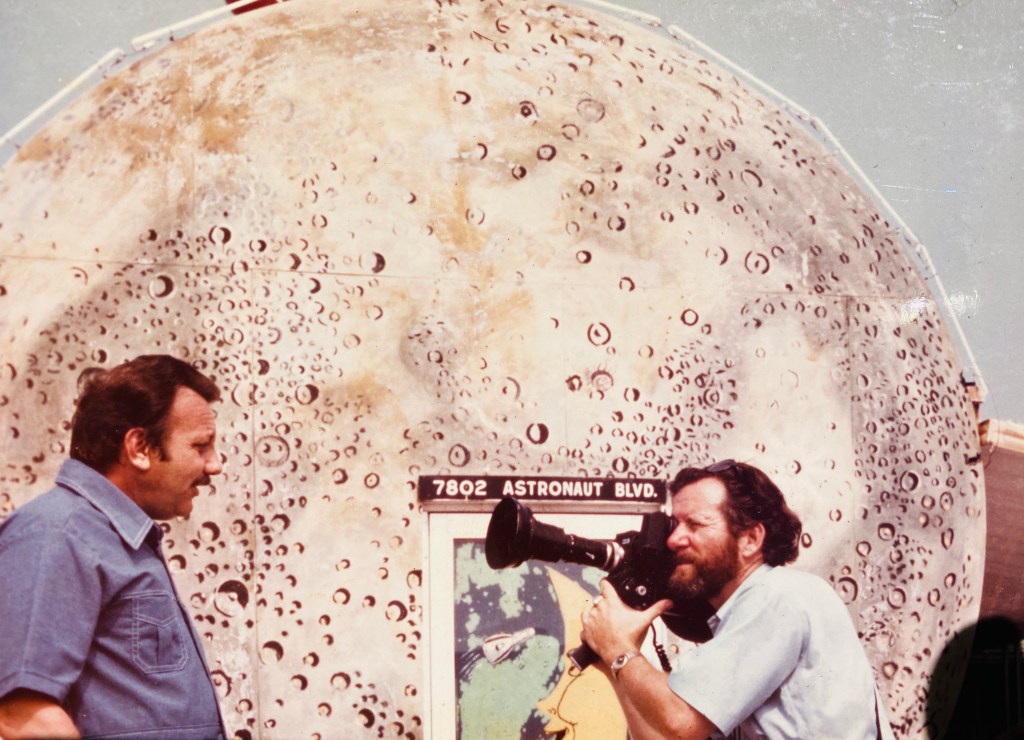

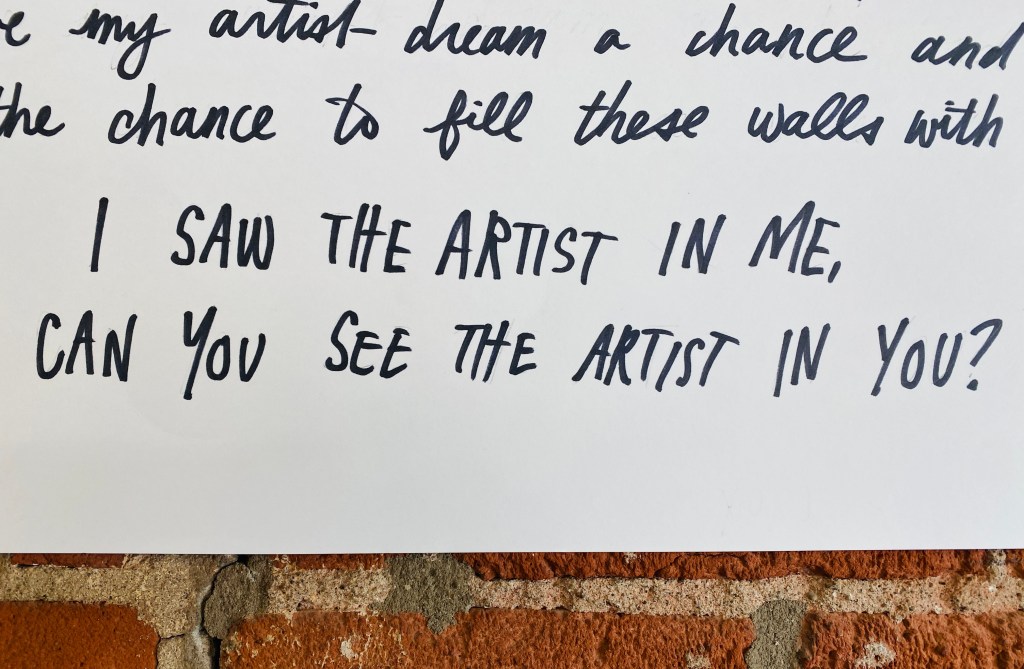

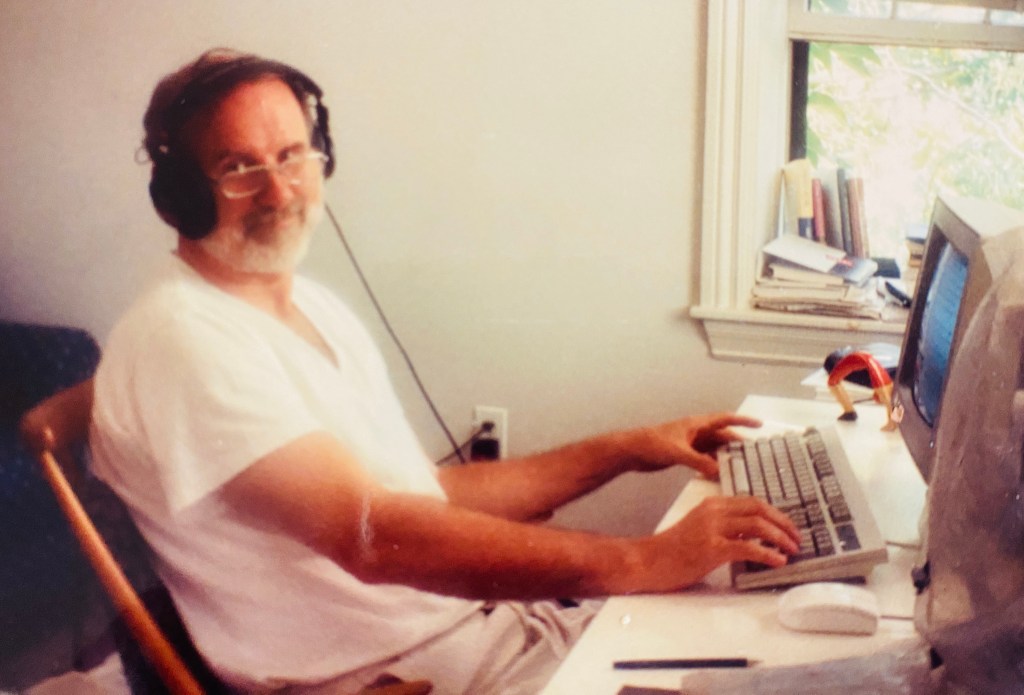

Because it is 1990 and the Internet is a mere twinkle in a few eyes, my journalist father is back in Boston, Massachusetts closely following the newswires and outlets covering the Nepali revolution. When I return home months later he hands me a collection of carefully cut-out press clippings tracking the progress of the contentious uprising raging along while I am on the other side of the world.